You need to know the rules before you can break the rules.

But do you?

The teachers in my district have been using an approach to grammar around suggested by Jeff Anderson in his Patterns of Power book and lessons. In this approach:

“…students study authentic texts and come to recognize these “patterns of power“—the essential grammar conventions that readers and writers require to make meaning.”

This means that instead of worksheets, students talk about a sentence or two in texts they are reading. They discuss the parts of speech and punctuation. They imitate the sentence(s) and share what they have written.

The use of model sentences from mentor texts is not a new practice. A meta-analysis conducted over 35 years ago (1984) by George Hillocks, Jr. titled “What Works in Teaching Composition: A Meta-Analysis of Experimental Treatment Studies,” confirmed the use of models as 22% more effective than grammar worksheets in isolation:

“This research indicates that emphasis on the presentation of good pieces of writing as models is significantly more useful in the study of grammar” (162).

There is a problem, however. Teaching grammar rules using model sentences from a mentor text is complicated. That is because authors, many of the authors we want students to read, do not follow some of the grammar rules.

You know the rules:

-

Never start a sentence with “And”, “But”, or “So.”

-

Use complete sentences only.

But, one does not have to look long to find examples of rule-breaking in many of the grade-level texts.

Coordinating Conjunctions: And, But, So

Looking for mentor texts in the upper elementary grade? The first chapter of Kate DiCamillo’s The Tiger Rising provides multiple examples of rule-breaking with sentences that begin the trifecta of coordinating conjunctions:

“But only for a minute; he was afraid to look at the tiger for too long, afraid that the tiger would disappear.”

“And he did not think about his mother.”

“So as he waited for the bus under the Kentucky Star sign, and as the first drops of rain fell from the sullen sky, Rob imagined the tiger on top of his suitcase, blinking his golden eyes, sitting proud and strong, unaffected by all the not-thoughts inside straining to come out.”

DiCamillo’s style can prove inconvenient for teachers in 3rd and 4th who are charged with teaching the use of coordinating conjunctions with dependent and independent clauses. How to explain such flagrant violations to students who are held to a different standard?

These teachers must either avoid the subject entirely or find other mentor texts.

The same disdain for a convention is seen in Madeleine L’Engle’s classic A Wrinkle in Time when the character of Calvin explains:

“When I get this feeling, this compulsion, I always do what it tells me. I can’t explain where it comes from or how I get it, and it doesn’t happen very often. But I obey it. And this afternoon I had a feeling that I must come over to the haunted house” (Ch 2).

The English author/poet Thomas Hardy is equally culpable. His Return of the Native might be offered to high school students in an Advanced Placement Literature class. They might need to defend how Hardy intentionally broke this convention in describing the setting of Egdon Heath:

“But celestial imperiousness, love, wrath, and fervour had proven to be somewhat thrown away on netherward Egdon” (Ch 1).

And Charles Dickens used a ‘So’ to start a sentence in his timeless classic, A Christmas Carol. In this passage, Scrooge waits for the visits that were promised by Jacob Marley.

“When Scrooge awoke, it was so dark, that looking out of bed, he could scarcely distinguish the transparent window from the opaque walls of his chamber. He was endeavouring to pierce the darkness with his ferret eyes, when the chimes of a neighbouring church struck the four quarters. So he listened for the hour” (Ch 3).

The flouting of conjunction rules is not limited to fiction. There are examples in literary nonfiction such as Rachel Carlson’s Silent Spring. In the New Yorker essay, a prequel to her book, Carlson employed began sentences with conjunctions, such as:

“There had been several sudden and unexplained deaths, not only among the adults but also among the children, who would be stricken while they were at play, and would die within a few hours. And there was a strange stillness.”

Even Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence, a document reviewed and voted upon by a committee breaks the rule. Of the 61 ‘and’s (roughly 4% of the text) in the Declaration, the placement of the last conjunction is what packs the punch:

“— And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of Divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor.”

Yes, yes. I know each of these authors broke the “and/but/so” convention to make a point. To contradict. To stress an idea. To break a reader’s rhythm. To startle.

They knew about the rule, and they broke it. Intentionally.

Then why are students not allowed the same choice?

Why might teachers doubt the intent of students as authors?

Use complete sentences only.

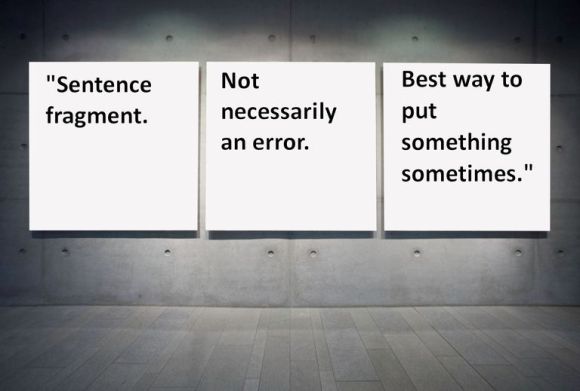

Students will also encounter another example of rule-breaking, incomplete sentences or sentence fragments. Incomplete sentences or rhetorical fragments can be found in texts at every grade level that students read in every genre.

The deliberate use of such sentence fragments could be a rhetorical device, such as an Anapodoton: “in which a stand-alone subordinate clause suggests or implies a subject.”

For young readers, Tammi Sauer (Author), Scott Magoon (Illustrator) the picture book Mostly Monsterly (2010) contains both sentence fragments…as well as sentences beginning with “And”:

“She liked to pick flowers. And pet kittens. And bake” (4-5)

Intermediate grade students may encounter sentence fragments in Maniac Magee:

“It was the day of the worms. That first almost-warm, after-the-rainy-night day in April, when you bolt from your house to find yourself in a world of worms. They were as numerous here in the East End as they had been in the West. The sidewalks, the streets. The very places where they didn’t belong. Forlorn, marooned on concrete and asphalt, no place to burrow, April’s orphans” (143).

As for those familiar texts in high school? In To Kill a Mockingbird, Harper Lee fragmented a critical sentence in Atticus Finch’s closing speech:

“She did something that in our society is unspeakable: she kissed a black man. Not an old Uncle, but a strong young Negro man” (Ch 20).

F. Scott Fitzgerald also closes The Great Gatsby with an incomplete thought, a fragmented ellipsis, as Nick recalls:

“Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter—to-morrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther.…And one fine morning—So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past“ (180).

There are examples of incomplete sentences used in nonfiction writing as well.

For example, the picture book Moonshot-the Flight of Apollo 11 (grades 2-5) by Brian Floca celebrates the 1969 historic moon landing telling the story in verse. In this text, the sentence fragments contain information in a poetic style:

“Here below

there are men and women

plotting new paths and drawing new plans.They are sewing suits, assembling ships,

and writing code for computers.Nuts and bolts, needles and thread,

and numbers, numbers, numbers.Thousands of people for,

millions of parts” (6).

For older students, Elie Wiesel’s memoir Night could be read during a study of the Holocaust. In Chapter Three, Wiesel painfully summarizes the last moment he saw his mother and sisters alive in the Auschwitz camp in a sentence fragment:

“Men to the left! Women to the right!” Eight words spoken quietly, indifferently, without emotion. Eight simple, short words.”

Advanced Placement Language and Composition students might note the liberal use of sentence fragments in essays, like the ones in the opening of award-winning sports columnist Rick Reilly’s article Sis! Boom! Bah! Humbug! published in Sports Illustrated (10/18/1999)

“Every Friday night on America’s high school football fields,

it’s the same old story. Broken bones. Senseless violence.

Clashing egos.Not the players. The cheerleaders.”

Okay. Again? Yes. I know.

A writer gets to break the rules. But when is that permission given to our student writers?

The English Journal: NCTE

Of course, teachers want to have students express themselves and develop a voice. An article Edgar H. Schuster wrote for the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) English Journal A Fresh Look at Sentence Fragments (5/2006) argues that some rules, such as no incomplete sentences, may discourage students from developing their voice or taking risks in their writing style. His research led him to counter grammar rules by saying:

- Native speakers of English have “intuitive knowledge” of what makes a sentence.

- Students often break the rules before they learn them; breaking rules may be a stage in learning them.

- How do teachers understand how a student knows “the rules”…or not?

Schuster cites another researcher, Rei R. Noguchi, who suggested that the kinds of fragments students write reveal that they understand syntax.

For example, Schuster offers a reflection by an eleventh-grader who opened her essay,

“Sweet sixteen. Ahhh . . . driver’s license, car, new found freedom and independence,”

According to Schuster, this student writer “was thinking in terms of effectiveness rather than grammar.”

He further argues that if such an example of a fragment is rhetorically effective, then how can the teacher applaud or rate some students—those who “know the rules”—and then penalize others?

Reliable Grammar rules

Instead of a list of ‘Don’ts’, the discussions teachers have with students in writing conferences about grammar rules may be more effective. This is what can happen when teachers use the mentor sentences and the format of Anderson’s Patterns of Power. At every grade level, students can identify the grammatical concept (ex: use of conjunctions), compare that concept, and then imitate that concept. They may imitate by starting a sentence with a conjunction or by creating a sentence fragment.

These discussions also allow students the chance to explain how an author’s choice impacts the reader’s understanding. In short, the goal is for more discussion about an author’s grammatical choices rather than a stack of worksheets that reinforce grammar rules that real authors do not follow.

So these rules? Not necessary.

In fact, writer-editor William Brohaugh (Everything in English is Wrong) once declared that the only reliable rule in writing is “Never start a sentence with a comma.”

(¡But be aware, there are sentences in Spanish that start with an upside-down exclamation point!)

Wonderful post. I thoroughly enjoyed it. All of it. And totally agree with William Brohaugh’s one reliable rule. But I’m thinking about it. 🙂

Funny! Thank you…tried to provide enough examples for each grade!!

I taught college composition classes for many years, and I now write K-12 education materials and write a blog on the logic of grammar. I enjoyed this post, but I want to point out that the “rule” not to begin a sentence with “and,” “but,” or “so” has been out of vogue for more than 40 years. The one rule that has remained constant is that a comma does not appear after “but” unless it is one of a pair setting of a restrictive clause (e.g., But, she clarified with a pointed look, it is perfectly acceptable to begin a sentence with any of these words. But do not follow “but” with a comma in every other circumstance.). Please don’t confuse your students by adding a comma after “but” or “and.” A comma is also rarely necessary after “so” or “then.” Grammar is much easier if you approach it logically rather than by memorization of rules. Hint to all teachers: Get a copy of Strunk & White’s Elements of Style and use it religiously. Incidentally, Strunk & White never mention not beginning a sentence with “and,” “but,” and “so,” and that grammar bible was published in 1959.

Thank you! I appreciate you taking the time to respond. I am considering how I should share your explanation with all of the high school/middle school teachers in my district who insist that college professors fail students who do not follow “rules.” For the record, I did check out Elements of Style, and I found a reference to a 1918 edition. But this post was so long that I did not include the following evidence:

“But whether the interruption be slight or considerable, he must never omit one comma and leave the other.”-Strunk & White