The Unit 1 pre-assessment question from Teachers College Reading units of Study Grade 4 asks:

How did the [character] change from the beginning to the end of the story and why? (Unit 1 -“Papa’s Parrot” by Cynthia Rylant.)

In previous posts, I questioned this kind of assessment that asks about character change in a story.

I have argued in these posts that in texts for the 3rd grade -and even in more sophisticated texts up through Grade 12- there may not be a character change.

In this assessment, the character in Rylant’s story does not change. His character is the same, but once he learns about the parrot, he experiences a change in his feelings towards his father…and the parrot.

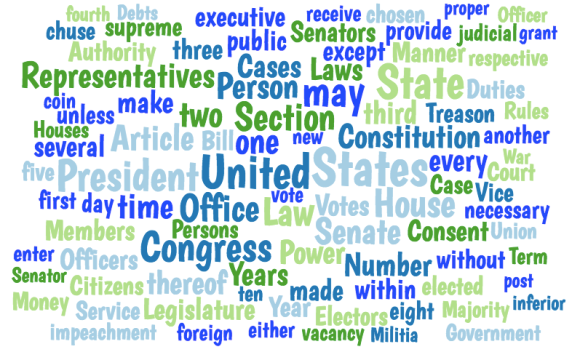

The character change question above may have been generated by a misread of the ELA Common Core State Standards. The Reading Literature Standard 6.4 (grade 6) states that students in grade 6 should be able to:

Describe how a particular story’s or drama’s plot unfolds in a series of episodes as well as how the characters respond or change as the plot moves toward a resolution.

It should be noted that the question asked above is not even part of a Grade 4 standard, nor does the question ask how a character responds.

The question also does not directly ask if the opinions or viewpoint of the character have evolved during the story. Readers may see such changes in the character’s sentiment or fortune or direction or purpose. Even in the most predictable book series for grade 4 readers, there could also be a change of mind, or stripes, or tune, or ways.

But a change in character?

Students in 4th grade will have several years to go before they meet the kinds of characters (usually British) who are radically altered by circumstance in the plot. They will have years before they meet Golding’s Jack (Lord of the Flies), Huxley’s John (Brave New World), and Milton’s Lucifer (Paradise Lost). They have more to read before they encounter the long list of Shakespeare’s radical transformations in the characters of Juliet, Macbeth, Richard III, Henry IV, etc.

Students in 4th grade will have several years to go before they meet the kinds of characters (usually British) who are radically altered by circumstance in the plot. They will have years before they meet Golding’s Jack (Lord of the Flies), Huxley’s John (Brave New World), and Milton’s Lucifer (Paradise Lost). They have more to read before they encounter the long list of Shakespeare’s radical transformations in the characters of Juliet, Macbeth, Richard III, Henry IV, etc.

And even with evidence of change on these heavy hitters, there are literary scholars who could still argue that the character is not so much changed but that character is revealed over the length of the text.

Perhaps the reason for any confusion on the subject of character change in stories comes the lack of understanding of what changes can happen in the character of real human counterparts. There have been numerous studies that try to answer the question, “Do people change?”

A report from Eileen K. Graham, et al. in 2017 (A Coordinated Analysis of Big-Five Trait Change Across 16 Longitudinal Samples) reviewed data on almost 50,000 people in the hopes of answering that question on changes in human personality. This meta-analysis looked for the common ground, between the belief in the 1970s that “personality is unstable for nearly everyone” (Mischel,1969, 1977) and the belief in the 1980-90’s that “personality is stable for nearly everyone”(Costa &McCrae, 1986; Costa & McCrae, 1980).

While sudden dramatic changes in personality are rare, Graham et al. found in the analysis that studies did reveal a change in certain aspects of human personality. These changes in people took time, over a course pf years or decades, not days or weeks.

“We conclude from our study that neuroticism, extraversion, conscientiousness, and openness go down over time, while agreeableness remains relatively stable.”

In other words, the study noted that agreeableness (or a lack of) in humans remains a constant personality trait. In humans, the other changes in personality traits-moodiness, sociability, carefulness, and tolerance- are measured as a loss.

This finding is contrary to what happens to characters in literature. In literature, characters experience some kind of gain, good or bad. Characters make a discovery, an anagnorisis, literally the Greek word for discovery. Anagnorisis is the transition in which a character may gain wisdom, knowledge, or maybe enlightenment. Even when the cost of experience results in punishment or in tragedy, the character gains a new understanding.

The character learns something.

So, back to the 4th grade to the question of about character change which has caused so much concern.

Texts that students can (or choose) to read independently at that grade level do not contain any character change. They can point to the popular Dork Diaries, Origami Yoda, Big Nate, Diary of a Wimpy Kid as examples.

While there is no change in character in any of these series, (the characters remain immature, sometimes shallow) these characters do learn important life lessons. These life lessons are intentionally directed at students who are themselves are learning as they move from innocence or ignorance to experience and knowledge.

The more sophisticated stories taught at the fourth-grade level, such as Tuck Everlasting or Hatchet, echo similar messages. In these novels, “You are good as you are” seems counter to the idea of character change, especially when coupled with a cautionary “learn from others” or “learn from your mistakes.”

The difference between “character change” and “what a character learns” can be a direct route to helping a student determine the book’s theme. The story’s theme is always tied to a character’s discovery (the anagnorisis), for example:

- Frindle (Andrew Clements) that language is flexible.

- Matilda (Roald Dahl) that adults don’t know everything.

- Esperanza Rising (Pam Munoz Ryan) that families who stick together can survive.

In each of these stories, it is not the character that changes, but the character’s thinking or feeling. Since the question of character change itself needs to change, the revised question for grade four students is:

“What does the character learn from the beginning to the end of the story, and why is this significant?”

Rephrasing the question to what the character learned can help students discover the message of a story, connecting how an author creates a character’s change of heart or a change of sides to the theme or message of the story.

Change may be good, but not in character questions.