On September 17, 1787, 41 delegates to the Constitutional Congress signed their names to the Constitution of the United States, and our government was born. In 2004, to honor this achievement, September 17th was named Constitution Day. This date offers an opportunity to meet a legislative requirement. According to the U.S. Department of Education:

Each educational institution that receives Federal funds for a fiscal year is required to hold an educational program about the U.S. Constitution for its students.

There are activities for September 17th or for other extended periods on a Constitution Day website, The extended activities allow students to have multiple exposures to this founding document.which can be a difficult read. An objective review based on vocabulary and sentence complexity shows the readability the document is at the 14.7-grade level, which means that most middle and high school students cannot read it independently without some support.

One way to support students before or during reading is to use a program called Word Sift which was designed to “help teachers manage the demands of vocabulary and academic language in their text materials.”

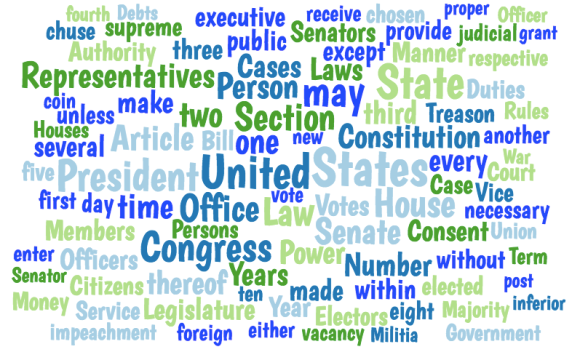

A teacher can copy and paste sections of the Constitution onto the Word Sift site to create a word cloud that identifies specific words that are repeated in the text. For example, pasting the language from the Preamble of the Constitution creates a word cloud (with 25/52 words) as seen below:

This word cloud visualizes how three frequently repeated words emphasize or clarify the main idea that is contained in the Preamble: “Establish United States.”

The same Word Sift can also sort the words alphabetically, and distinguish which words are found on a general academic vocabulary list (highlighted blue):

A visual analysis of word frequency of the first ten articles of the Constitution shows the word “states” used the most frequently -76 times in 45 sentences. The Word Sift of these articles below also shows the frequency of the word “united,” and highlights in bold other repeated words “right” (ten times), “law”(nine times) and “power” (eight times).

Using the Word Sift, teachers can prepare students for reading the sections of the Constitution by reviewing the content-specific vocabulary (president, electors, impeachment, judicial) in advance and by showing the connection between repeated language and the document’s purpose/message.

While word cloud programs are common on the Internet, the Word Sift program offers a feature that identifies and sorts lists of words according to academic discipline (math, science, ELA, and social studies).

Also, the words from any document pasted into the program can be sorted for English learners (EL) according to the New General Service List (NGSL). The words on the NGSL are the most important high-frequency words of the English language. There are 2800 words on the NGSL list and knowing these words will give EL students familiarity with more than 90% of most texts in English.

A teacher that uses a Word Sift of the Constitution can identify 28 words from the 2800 words of the NGSL (ex: may, enter, necessary, receive). These words are highlighted in bright blue in the illustration below:

In addition to targeting language by discipline or by academic word list, another Word Sift feature is an embedded Visual Thesaurus® with a limited image-search feature. The Word Sift site explains that a “Visual Thesaurus word web” is displayed when the cursor hovers over a highlighted word in the word cloud. For example, a screenshot of the Visual Thesaurus illustration of the word “UNITED ” is below (NOTE: visualization of selected word is interactive only on the Word Sift site):

This Visual Thesaurus feature can quickly show different meanings of the same word as well as antonyms.

Teachers may also want to use Word Sift in a review of the letter that George Washington wrote as he presided over the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. His Letter from George Washington to the Confederation Congress, accompanying the Constitution, September 17, 1787, expresses his support of the document. In the letter, he reflects on the compromises that were made in creating the Constitution, and his sentiments could be used in discussing current Constitutional issues as a WWGD? (What Would George Do?). He writes:

“It is at all times difficult to draw with precision the line between those rights which must be surrendered, and those which may be preserved; and, on the present occasion, the difficulty was increased by a difference among the several States as to their situation, extent, habits, and particular interests…”

Difficulty? Surrendered? Differences? Interests? The language of Washington’s letter can remind students of how the US Constitution has been used to address the divisive problems of the past and consider how the document guides the controversies of the present.

Using the program Word Sift to familiarize students with the vocabulary of the Constitution-or any other primary source document- can better prepare students for reading and exploring the text independently. The creators of Word Sift note:

We would be happy if you think of it playfully – as a toy in a linguistic playground that is available to instantly capture and display the vocabulary structure of texts, and to help create an opportunity to talk and explore the richness and wonders of language!