My school district recently purchased a class set of the March Trilogy, the graphic novel memoir that recounts the experiences of Congressman John Lewis (5th District, Georgia) in America’s struggle for civil rights including the marches from Selma to Montgomery. The comic book-style illustrations are engaging and some may mistake the memoir as something for children. Lewis’s experiences in the 1950-60s, however, were marked by violence, so the memoir is recommended for more mature audiences (grades 8-12).

The publisher, Top Shelf Productions, prepares audiences about the violence and language in the memoir by stating:

“…in its accurate depiction of racism in the 1950s and 1960s, March contains several instances of racist language and other potentially offensive epithets. As with any text used in schools that may contain sensitivities, Top Shelf urges you to preview the text carefully and, as needed, to alert parents and guardians in advance as to the type of language as well as the authentic learning objectives that it supports.”

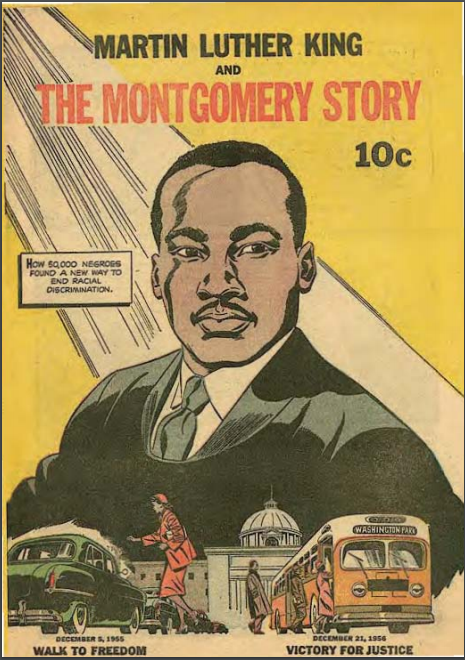

The March Trilogy is the collaboration between Congressman Lewis, his Congressional staffer Andrew Aydin, and the comic book artist, Nate Powell. Their collaboration project began in 2008 after Congressman Lewis described the powerful impact a 1957 comic book titled Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story had on people like himself who were engaged in the Civil Rights Movement. The comic book has been reissued by the original publisher,

The 1957 comic book is also available as a PDF by clicking on a link available on the Civil Rights Movement Veterans (CRMV) website. The About page on this site has the following purpose statement in bold:

This website is created by Veterans of the Southern Freedom Movement (1951-1968). It is where we tell it like it was, the way we lived it, the way we saw it, the way we still see it.

Under this explanation is the blunt statement: “We ain’t neutral.”

The decision to publish the Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story as a comic book in the late 1950s is a bit surprising. At that time the genre of comic books in America had come under scrutiny. A psychiatrist, Fredric Wertham, made public his criticisms that comic books promoted deviant behavior. That claim in 1954 led to the creation of a Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency along with the Comics Code Authority (CCA). That Authority drafted the self-censorship Comics Code that year, which required all comic books to go through a process of approval.

In 1958, the Friends of Reconciliation published the 16-page comic book as a challenge to CCA restrictions. An artist from the Al Capp Studios, creators of Li’l Abner, donated time to illustrate the book. Benton Resnick, a blacklisted writer, wrote the text. He concluded with a promotion for the “thousands of members throughout the world [who] attempt to practice the things that Jesus taught about overcoming evil with good.” The Friends of Reconciliation’s religious message passed the scrutiny of Senate Subcommittee.

The comic book also received Dr. King’s approval who called it “an excellent piece of work” that did a “marvelous job of grasping the underlying truth and philosophy of the movement.”

Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story was distributed through churches, universities, social justice organizations and labor unions during the Civil Rights Movement. Now in reproduction, the comic book has been widely circulated to support international struggles for civil rights, including Egypt’s Tahrir’s Square.

Teachers can use this primary source comic book as a way to explain how nonviolent protests held throughout the South contributed to the Civil Rights Act of 1964. One of the first frames in the book holds a proclamation:

“In Montgomery, Alabama, 50,000 Negroes found a new way to work for freedom, without violence and without hating.”

Several frames later, there are illustrations showing Rosa Parks’s arrest when she refused to give up her seat on the bus in Montgomery, Alabama. These events are narrated by a fictional character named “Jones”. His role is to introduce the reader to the 29-year-old Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr, a preacher from the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. Dr. King will become the charismatic leader who planned the bus boycotts in Montgomery.

In the comic book, several frames show how protesters rehearsed for confrontations during protests. King wanted protesters to practice the tenets of non-violence the same way that Mahatma Gandhi had used non-violence in liberating India from the British Empire.

The “Montgomery Method” that Dr. King promotes in the strip is based on religion; God is referenced as the motivating force. An explanation of the different steps to follow the method of non-violence begins with the statement that God “says you are important. He needs you to change things.”

In the concluding pages, the comic book also has suggestions for activists that were used to guide those who worked for civil rights in the 1950s -1960s. Some of these suggestions are remarkably timely, and they could be used in class discussions:

Be sure you know the facts about the situation. Don’t act on the basis of rumors, or half-truths, find out;

Where you can, talk to the people concerned and try to explain how you feel and why you feel as you do. Don’t argue; just tell them your side and listen to others. Sometimes you may be surprised to find friends among those you thought were enemies.

This comic book Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story can be used to prepare students for the graphic novel memoir by Congressman Lewis, a veteran of the Civil Rights Movement. While he is not directly named in the 1957 comic book, he participated in many of the events and his memoir March provides another point of view to major events.

In Lewis’s recounting, March: Book I is set up as a flashback in which he remembers the brutality of the police on the Edmund Pettus Bridge during the 1965 Selma-Montgomery March. The second book, March: Book 2 (2015) highlights the Freedom Bus Rides and Governor George Wallace’s “Segregation Forever” speech. The final book, March: Book 3 (2016) includes the Birmingham 16th Street Baptist Church bombing; the Freedom Summer murders; the 1964 Democratic National Convention; and the Selma to Montgomery marches. March: Book 3 received multiple awards including 2016 National Book Award Winner for Young People’s Literature, the 2017 Printz Award Winner, and the 2017 Coretta Scott King Author Award Winner.

In receiving these awards, Lewis restated his purpose that his memoir was directed toward young people, saying:

“It is for all people, but especially young people, to understand the essence of the civil rights movement, to walk through the pages of history to learn about the philosophy and discipline of nonviolence, to be inspired to stand up to speak out and to find a way to get in the way when they see something that is not right, not fair, not just.”

He could just as well have been speaking about Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story. They may belong to the genre of comic books, but they also are serious records of our history.