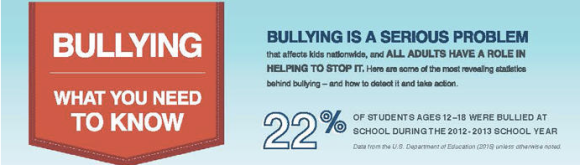

This April 1865 photo provided by the Library of Congress shows President Abraham Lincoln\’s box at Ford\’s Theater, the site of his assassination. Under the headline “Great National Calamity!” the AP reported Lincoln’s assassination, on April 15, 1865. (AP Photo/Library of Congress)

News stories are generally written in what is commonly known as the inverted pyramid style, in which the opening paragraph features the “5 Ws” of journalism: Who, What, Where, When, Why, and How. The reason for this style is so that the reader gets the most important information up front. Given the amount of time readers have today to read the amount of news generated in a 24 hour news cycle, the inverted pyramid makes sense.

In contrast, 150 years ago a dispatch by the Associated Press took a storytelling approach when President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination at the hands of John Wilkes Booth was relayed by AP correspondent Lawrence Gobright. Under the headline”Great National Calamity!” he chose to deliver gently the monumental news of Lincoln’s death in paragraph 9:

The surgeons exhausted every effort of medical skill, but all hope was gone.

The Common Core State Standards in Literacy promotes primary source documents, such as this news release, in English Language Arts and Social Studies. Documents like this provide students an opportunity to consider the voice or point-of-view of a writer within a historical context.

In this 19th Century AP news release, an editor’s note attached described in vivid detail Gobright’s efforts to gain first-hand information in compiling the story of Lincoln’s assassination. In the tumult that followed the assassination, Gobright became more than a witness as he:

scrambled to report from the White House, the streets of the stricken capital, and even from the blood-stained box at Ford’s Theatre, where, in his memoir he reports he was handed the assassin’s gun and turned it over to authorities.

This circa 1865-1880 photograph provided by the Library of Congress’ Brady-Handy Collection shows Lawrence A. Gobright, the Associated Press’ first Washington correspondent.. Under the headline “Great National Calamity!” the AP reported President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, on April 15, 1865. (AP Photo/Library of Congress)

Gobright’s opening line for the news story identified the setting as Ford’s Theatre; he then added information of considerable interest to the Union Army, that:

It was announced in the papers that Gen. Grant would also be present, but that gentleman took the late train of cars for New Jersey.

After setting up who was or was not in attendance, Gobright detailed the sequence of events in paragraph 3:

During the third act and while there was a temporary pause for one of the actors to enter, a sharp report of a pistol was heard, which merely attracted attention, but suggested nothing serious until a man rushed to the front of the President’s box, waving a long dagger in his right hand, exclaiming, ‘Sic semper tyrannis,’

Describing the assailant’s escape on horseback, Gobright concluded the reaction of the crowd in the audience in paragraph 4 in an understatement, “The excitement was of the wildest possible description…”

His AP’s edited version online states that the report does not contain details on the second assassination report on Secretary of State William Seward. There is his reference to the other members of Lincoln’s cabinet who, after hearing about the attack on Lincoln, travelled to the deathbed:

They then proceeded to the house where the President was lying, exhibiting, of course, intense anxiety and solicitude.

As part of a 150 year memorial tribute, the AP offers two websites with Gobright’s report, the first with an edited version of the report and the second, an interactive site with graphics. The readabilty score on Gobright’s release is a grade 10.3, but with some frontloading of vocabulary (solicitude, syncope) this story can be read by students in middle school. There are passages that place the student in the moment such as:

- There was a rush towards the President’s box, when cries were heard — ‘Stand back and give him air!’ ‘Has anyone stimulants?’

- On an examination of the private box, blood was discovered on the back of the cushioned rocking chair on which the President had been sitting; also on the partition and on the floor.

The NYTimes reporting of the assassination, having the advantage of several hours start, did not bury the lede, or begin with details of secondary importance, offering the critical information through a series of headlines beginning with the kicker “An Awful Event”:

An Awful Event

The Deed Done at Ford’s Theatre Last Night.

THE ACT OF A DESPERATE REBEL

The President Still Alive at Last Accounts.

No Hopes Entertained of His Recovery.

Attempted Assassination of Secretary Seward.

DETAILS OF THE DREADFUL TRAGEDY.

Their six column spread allowed space for the six drop heads, or smaller secondary headlines, above that were stacked to provide an outline of the events. The article that follows begins with then Secretary of War Edwin Stanton’s message to Major General Dix, April 15, 1865 at 1:30 AM:

This evening about 9:30 PM, at Ford’s Theatre, the President while sitting in his private box, with Mrs. Lincoln, Mrs. Harris, and Major Rathburn, was shot by an assassin who suddenly entered the box and approached behind the President.

Stanton’s 324 word report has a readability grade 7.2, and includes also details about the other assassination attempt on Seward’s life:

About the same hour an assassin, whether the same or not, entered Mr. SEWARD’s apartments, and under the pretence of having a prescription, was shown to the Secretary’s sick chamber. The assassin immediately rushed to the bed, and inflicted two or three stabs on the throat and two on the face.

A second dispatch features Gobright’s reporting and appears below Stanton’s message in the second column. Following these accounts, a third dispatch by an unnamed reporter is dated Friday, April 14, 11:15 P.M. and like Gobright’s account begins with a storybook-type lead:

A stroke from Heaven laying the whole of the city in instant ruins could not have startled us as did the word that broke from Ford’s Theatre a half hour ago that the President had been shot. It flew everywhere in five minutes, and set five thousand people in swift and excited motion on the instant.

These first-person accounts of Gobright, Stanton, and others covering Lincoln’s assassination will allow students to contrast what they recognize as the reporting styles of today with an example of the storytelling reporting style 150 years ago. Students can analyze both styles for conveying information, and then comment on impact each style may have on an audience.

More important is the opportunity to ditch the dry facts from a textbook, as these newspaper releases allow students to discover that at the heart of stories about Lincoln’s assassination, the reporters were really storytellers, and their hearts were breaking.