The release of the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) Progress Report for 2012 (“Nation’s Report Card”) provides an overview on the progress made by specific age groups in public and private schools in reading and in mathematics since the early 1970s. The gain in reading scores after spending billions of dollars, countless hours and effort was a measly 2% rise in scores for 17-year-olds. After 41 years of testing, the data on the graphs show a minimal 2% growth. After 41 years, Einstein’s statement, “Insanity is doing the same thing repeatedly and expecting different results,” is a confirmation that efforts in developing effective reading programs have left the education system insane.

The rather depressing news from NAEP in reading scores (detailed in a previous blog) could be offset, however, by information included in additional statistics in the report. These statistics measure the impact of “reading for fun” on student test scores. Not surprisingly, the students who read more independently, scored higher. NAEP states:

Results from previous NAEP reading assessments show students who read for fun more frequently had higher average scores. Results from the 2012 long-term trend assessment also reflect this pattern. At all three ages, students who reported reading for fun almost daily or once or twice a week scored higher than did students who reported reading for fun a few times a year or less

The irony is that reading for fun is not measured in levels or for specific standards as they are in the standardized tests. For example, the responses in standardized tests are measured accordingly:

High Level readers:

- Extend the information in a short historical passage to provide comparisons (CR – ages 9 and 13)

- Provide a text-based description of the key steps in a process (CR)

- Make an inference to recognize a non-explicit cause in an expository passage (MC – age 13)

- Provide a description that includes the key aspects of a passage topic (CR – ages 9 and 13)

Mid Range Readers:

- Read a highly detailed schedule to locate specific information (MC – age 13)

- Provide a description that reflects the main idea of a science passage (CR – ages 9 and 13)

- Infer the meaning of a supporting idea in a biographical sketch (MC – ages 9 and 13)

- Use understanding of a poem to recognize the best description of the poem’s speaker (MC)

Low Level Readers:

- Summarize the main ideas in an expository passage to provide a description (CR – ages 9 and 13)

- Support an opinion about a story using details (CR – ages 9 and 13)

- Recognize an explicitly stated reason in a highly detailed description (MC)

- Recognize a character’s feeling in a short narrative passage (MC – age 13)

(CR Constructed-response question /MC Multiple-choice question)

Independent reading, in contrast, is deliberately void of any assessment. Students may choose to participate in a discussion or keep a log on their own, but that is their choice. The only measurement is a student’s willingness to volunteer the frequency of their reading, a form of anecdotal data.

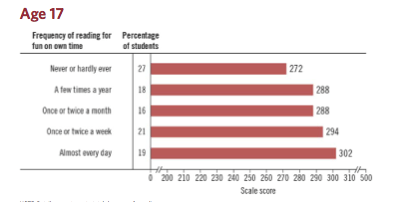

According to the graph below (age 17 only), students who volunteered that they read less frequently were in the low to mid-level ranges in reading. Students who volunteered that they read everyday met the standards at the top of the reading scale.

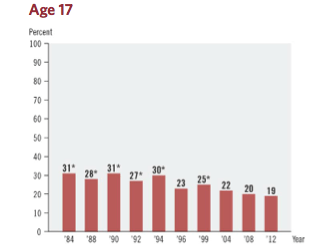

Sadly, this NAEP data recorded a decline in reading for fun over the last 17 years-exactly the age of those students who have demonstrated only a 2% increase in reading ability. The high number of independent readers (“reading for fun”) was in 1994 at 30%.

So what happened the following years, in 1995 and 1996, to cause the drop in students who read voluntarily? What has happened to facilitate the steady decline?

In 1995 there were many voices advocating independent reading: Richard Allington, Stephen Krashen, and Robert Marzano. The value of independent reading had been researched and was being recommended to all districts.

Profit for testing companies or publishing companies, however, is not the motive in independent reading programs.There are no “scripted” or packaged or leveled programs to offer when students choose to “read for fun”, and there is no test that can be developed in order to report a score on an independent read. The numerical correlation of reading independently and higher test scores (ex: read 150 pages=3 points) is not individually measurable; and districts, parents, and even students are conditioned to receiving a score. Could the increase of reading programs from educational publishers with leveled reading box sets or reading software, all implemented in the early 1990s, be a factor?

Or perhaps the controversy on whole language vs. phonics, a controversy that raged during the 1990s, was a factor? Whole language was increasingly controversial, and reading instructional strategies were being revised to either remove whole language entirely or blend instruction with the more traditional phonics approach.

The sad truth is that there was plenty of research by 1995 to support a focus on independent “reading for fun” in a balanced literacy program, for example:

- The Six Ts of Effective Elementary Literacy Instruction by Richard Allington (1995)

- The Power of Reading: Insights from the Research by Stephen Krashen (1993; revised 2004)

- Teaching Children to be Literate Anthony V. Manzo, Ula Casale Manzo (1995)

- New Approaches to Literacy: Helping Students Develop Reading and Writing Skills. (1995) Robert J. Marzano, D. E. Paynter,

Yet seventeen years later, as detailed in the NAEP report of 2012, the scores for 17-year-old students who read independently for fun dropped to the lowest level of 19%. (chart #2)

While the scores from standardized testing over 41 years according to the NAEP report show only 2% growth in reading, the no cost independent “reading for fun” factor has proven to have a benefit on improving reading scores. Chart #1 shows a difference of 30 points out of a standardized test score of 500 or a 6% difference in scores between students who do not read to those who read daily. Based on the data in NAEP’s report, reading programs have been costly and yielded abysmal results, but letting students choose to “read for fun” has been far less costly and reflects a gain in reading scores.

The solution to breaking this cycle is given by the authors of The Nation’s Report Card. Ironically, these authors are assessment experts, data collectors, who have INCLUDED a strategy that is largely anecdotal, a strategy that can only be measured by students volunteering information about how often they read.

The choice to include the solution of “reading for fun” is up to all stakeholders-districts, educators, parents, students. If “reading for fun” has yielded the positive outcomes, then this solution should take priority in all reading programs. If not, then we are as insane as Einstein said; in trying to raise reading scores through the continued use of reading programs that have proven to be unsuccessful, we are “doing the same thing repeatedly and expecting different results.”