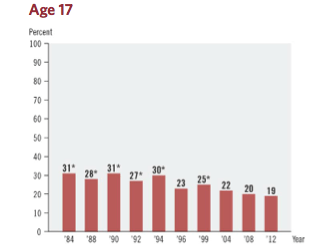

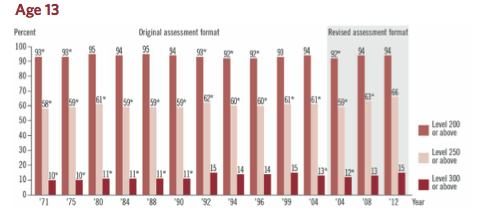

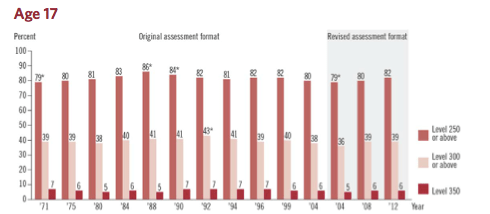

This past week, I wrote a blog post that critiqued the results of The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) 2013 test. There was a 2% growth in reading scores over the past 41 years for students at age 17.

A 2% increase.

That’s all.

Billions of dollars, paper piles of legislation, incalculable time…..and the result has been an abysmal 2% increase.

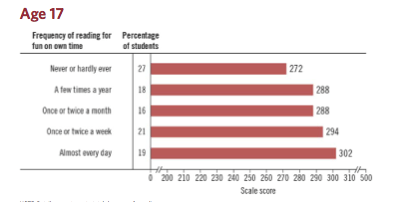

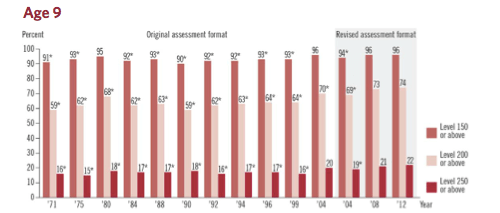

In a subsequent post, I wrote how NAEP also provided data to prove independent reading was the key to improving test scores. NAEP reported that students who claimed to read for fun scored higher on standardized tests with the obvious conclusion that the more time a student spent reading, the higher the student’s score. This information, included in a report that demonstrated a failure of reading programs, offered a possible solution for increasing reading scores: adopt a no-cost, read for fun initiative in order to improve results.

I tweeted out the the link to my post:

2013 NAEP Tests show only 2% growth in reading by age 17 UNLESS students “read for fun”

I received this tweet in response:

http://www.reading-rewards.com is a lovely site to use when you want to encourage kids to read for fun

So, I went to the Reading Rewards website, but I had some concerns. The headline banner read:“The Reward is in the Reading”, certainly a noble sentiment. However, below this banner was the text that read:

Parents & Teachers:

We know all about the rewards that reading offers, but sometimes our more reluctant readers need a little extra incentive. The Reading Rewards online reading log and reading incentive program helps make reading fun and satisfying. Find more about Reading Rewards’s benefits for parents and teachers.

The concept of an incentive program or reading for “rewards” is not reading for fun. Reading for pleasure should be the only incentive, and offering incentive programs can be counter-productive. Consider education advocate Alfie Kohn‘s explanation of his research that illustrates why incentivized reading programs are not successful:

The experience of children in an elementary school class whose teacher introduced an in-class reading-for-reward program can be multiplied hundreds of thousands of times:

The rate of book reading increased astronomically . . . [but the use of rewards also] changed the pattern of book selection (short books with large print became ideal). It also seemed to change the way children read. They were often unable to answer straight-forward questions about a book, even one they had just finished reading. Finally, it decreased the amount of reading children did outside of school.

Notice what is going on here. The problem is not just that the effects of rewards don’t last. No, the more significant problem is precisely that the effects of rewards do last, but these effects are the opposite of what we were hoping to produce. What rewards do, and what they do with devastating effectiveness, is to smother people’s enthusiasm for activities they might otherwise enjoy.

Kohn’s explanation in his A Closer Look at Reading Incentive Programs (Excerpt from Punished by Rewards 1993/1999) illustrates the problems that develop for late middle school and high school teachers (gr 7-12) experience once elementary students have experienced a reward program with their reading. Students who are conditioned to read for any kind of reward develop a Pavlovian response. They learn to expect a reward; once the reward is removed, however, they lose interest.

Sadly, most students are already in a “quid pro quo” educational experience. Even in elementary school, students are conditioned to want a grade for every activity. Matt Groening, creator of The Simpsons poked fun of this conditioned response for constant feedback in one episode when Springfield’s teachers went out on strike, and a distraught Lisa begged her mother, Marge, to “grade her”:

“Grade me! Look at me! Evaluate and rank me!

I’m good, good, good and oh so smart!

GRADE ME!”

While grades are not the currency for this website, Reading Rewards is perfectly positioned to be a commercial enterprise with language on the site promoting the RR “store” and “e-commerce”. This initial shopping experience may be for some trinket in a teacher’s box, a homework pass, or a pizza party, but the potential for “shopping” on this site is certainly a possibility.

Here is the promotional text for teachers:

The website advises teachers what items to have for students to “purchase”, and even suggests major retailers i-Tunes and Amazon:

Reward Ideas

Teachers and parents can create any reward they want and define how many RR miles are required to “purchase” each reward. Here are some ideas of Rewards selected by many of our users:

- Movie night at home

- Movie in the theater

- Family game night

- Sleepover with friends

- Trip to the dollar store

- Prize draw from a treasure box

- Extra tickets for a classroom raffle

- The right to choose the dessert after dinner

- Make/decorate/eat cupcake session

- Amazon credit

- iTunes credit

- Game console time

Again, Kohn believes that in teaching students to read, incentives should not be used. Instead he notes:

But what matters more than the fact that children read is why they read and how they read. With incentive-based programs, the answer to “why” is “To get rewards,” and this, as the data make painfully clear, is often at the expense of interest in reading itself.

So while the key to independent reading is the key to raising reading scores, students should not be raising profits for software companies as well. There are other features on this software that are admirable. The site includes places for reading logs, creating reading wish lists, and peer sharing reviews, but those features could be accomplished on a (free) blog or wiki without the distractions of prizes or rewards.

I do not fault the teacher who was well-intended when she tweeted out this website. She wants students to read for fun. The NAEP report proves that independent reading can effectively raise scores when the reading is self-motivated reading for pleasure. Teachers should question, however, when reading for fun is linked to reading with “funds”.

I was surprised that the play was paired with Of Poseidon, a romantic fantasy involving a independent and beautiful Emma and her strange encounters with the incredibly handsome Gaylen. I would have paired this book with Romeo and Juliet because the inferences about clan conflicts are too frequent not to imagine “two houses both alike in dignity, in the fair ocean where we lay our scene.” This debut novel by Anna Banks addresses mermaid lore, the legend of Atlantis, and forbidden love on the Jersey Shore. Unlike the TV show, listeners are 75% into the book before the first kiss; there is a great deal of “raising her chin with his fingers” and “cheek-stroking” to keep romantics hopeful. The reader (Rebecca Gibel) was also excellent, lacing some of the more exclamatory phrases with the right amounts of sarcasm or ruefulness. My only complaint was that this novel is the first in a series. As I got closer to the end of the recording, I began to realize that this novel was the “introductory”, a sentiment seconded by this reviewer:

I was surprised that the play was paired with Of Poseidon, a romantic fantasy involving a independent and beautiful Emma and her strange encounters with the incredibly handsome Gaylen. I would have paired this book with Romeo and Juliet because the inferences about clan conflicts are too frequent not to imagine “two houses both alike in dignity, in the fair ocean where we lay our scene.” This debut novel by Anna Banks addresses mermaid lore, the legend of Atlantis, and forbidden love on the Jersey Shore. Unlike the TV show, listeners are 75% into the book before the first kiss; there is a great deal of “raising her chin with his fingers” and “cheek-stroking” to keep romantics hopeful. The reader (Rebecca Gibel) was also excellent, lacing some of the more exclamatory phrases with the right amounts of sarcasm or ruefulness. My only complaint was that this novel is the first in a series. As I got closer to the end of the recording, I began to realize that this novel was the “introductory”, a sentiment seconded by this reviewer: