Jack Gantos stood on the steps of the altar at NYC Riverside Chapel blinking through large black glasses as he addressed the large crowd of educators who sat eager to hear him speak, “I feel compelled to throw a little fairy dust teaching into this…to educate and illuminate simultaneously.” Then, looking back at the large screen that projected the cover of his Newbery Award winning book, Dead End in Norvelt, he grinned broadly, “Yes, I wrote this book!”

Jack Gantos was the final keynote speaker at the Teachers College 83rd Saturday Reunion on Saturday, October 27th, and he was clearly enjoying this opportunity to talk about his evolution as a reader and as a writer. The large screen projected other images, handwritten notes and neatly drawn “spy” maps. “Here are some pages from a journal I kept,” explained Gantos, “ and you should know, that the boy that wrote this journal in fifth grade is the same man who writes today.” And write he does. Gantos is the author of the Rotten Ralph series and several books dedicated to the character Joey Pigza. In addition to this most recent Newbery Award, Gantos has also won Michael L. Printz and Robert F. Sibert honors, and he has been a National Book Award Finalist.

“The very first award you give yourself to set the bar high,” he intoned earnestly. “What everybody needs to do is to honestly come to some sense of literary standards, and those standards are defined by your reading.”

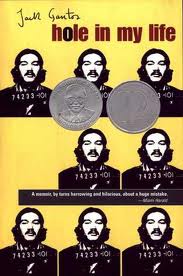

As a teacher, I am most familiar with Gantos’s memoir A Hole in My Life, which is a core text for our 12th grade Memoir elective. At 208 pages, the small paperback is much less intimidating than other memoirs, but its small size packs an amazing punch. With brutal honesty, Gantos details the year when just out of high school he became involved in smuggling drugs, and how he survived his prison sentence. A pattern of his prison mug shots covers the front of the text, and Gantos remarks about that picture early in the memoir:

As a teacher, I am most familiar with Gantos’s memoir A Hole in My Life, which is a core text for our 12th grade Memoir elective. At 208 pages, the small paperback is much less intimidating than other memoirs, but its small size packs an amazing punch. With brutal honesty, Gantos details the year when just out of high school he became involved in smuggling drugs, and how he survived his prison sentence. A pattern of his prison mug shots covers the front of the text, and Gantos remarks about that picture early in the memoir:

“The prisoner in the photograph is me. The ID number is mine. Th ephoto was taken in 1972 at the medium-security Federal Correctional Institution in Ashland, Kentucky. I was twenty-one years old and had been locked up for a year already -the bleakest year of my life-and I had more time ahead of me” (3).

The memoir also chronicles Gantos’s development as a writer, and how, “dedicating himself more fully to the thing he most wanted to do helped him endure and ultimately overcome the worst experience of his life.” (Amazon)

I have one class set (30) of these memoirs, and I occasionally find additional copies at used book sales which indicates that the book is often assigned for summer reading.

When they read A Hole in My Life, many students have strong reactions to the prison scenes, which take place in the last third of the memoir. “This is NOT a kid’s book,” more than one of them has told me, “this guy cannot be a children’s author!” They are notorious for trying to “protect” younger readers from any sordid incidents recounted in a book, and Gantos spares no details in describing some of the violent injuries he witnessed while working in the prison’s hospital ward. A Hole in My Life carries differences in age recommendations. Publisher’s Weekly suggests ages 12 and up, the book is a 2003 Bank Street – Best Children’s Book of the Year, and the Amazon recommendation is for ages 14 and up.

During his address, Gantos talked about the importance talking to teachers and students had in his creative process. Pointing to a picture of the cover, he said proudly, “This is the book that gets me into the front door of some high school where I can I get to talk about books and writing. This book is just like a key where I get to meet those high school kids.”

Usually, I usually assign the memoir to be read and discussed in literature circles and frequently students take these instructions to simply restate plot, “what happened? What happened next?” However, since Gantos was eager to share his structure with his audience, I may employ this strategy with this text. “When you think about a story,” he paused to show a graph projected on the big screen, ”you don’t think about the 50% invisible side called the structure. When I write, I draw 16 boxes and I fill them” he gestured to his sketches, “Beginning, middle,…action, story, character,” proving to this audience that their time pushing graphic organizers onto their students is still a worthwhile endeavor. As for the ending? “A book always has a double ending; the first is the physical ending, but the second is the emotional ending.” This is true in A Hole in My Life. Gantos relates the heartbreaking loss of his prison diary, written in between the lines of The Brother’s Karamazov, Gantos sharing the page space with the words of Dostoevsky. This diary was the more expensive the price to pay for his felonious actions, not the physical time he had spent behind bars.

He explained to his audience, “the reader wants to know how has the character been changed by an experience…the reader wants to have been inspired.” Gantos continued with more passion as he continued, “You read a book, and the next day, the book will be the same, but that you won’t. The that book will infects you and add to that little Library of Congress you have in your head.”

Gantos’s use of the Library of Congress, with the marble and beautiful domed ceiling as a metaphor for the reader’s brain is particularly vivid. The Library of Congress is the largest library in the world, with millions of books, recordings, photographs, maps and manuscripts in its collections. That powerful image is one every teacher in the room hopes for their students. After all, what could be better than producing a nation of graduates who have the resources of Library of Congress readily available in their brains?

Students look at their playing cards.

Students look at their playing cards.