If nothing else, the Common Core State Standards’ (CCSS) contribution to the academic lexicon will be the renaming of the genre known as non-fiction to a larger genre of informational texts. This renaming expanded the genre to include many forms of reading: textbooks, letters, speeches, maps, brochures, memoirs, biographies, and news articles, to name a few.

So where to find these informational texts? What is appetizing enough to make middle school students want to read a story, and then, answer the questions to check their understanding? What kind of high interest texts appeal to high school students who prefer to “Google” or “Sparknote” answers rather than read a text closely? What multi-media elements could be added to make an informational text palatable enough to be consumed by all levels of readers?

Well, teachers should look no further than the October 1, 2013, New York Times‘ feature article dedicated to Doritos Tortilla Chip titled That Nacho Dorito Taste. This short feature article combined photography and graphics; a short video: and even shorter text that combined to provide an explanation on how this particular food is engineered so that “you can’t eat just one.”

The article is timely since the CCSS requires that the student diet of reading should be 70% informational texts and 30% fiction by the time they graduate from high school. The Literacy Standards specifically address reading in math, science, social studies, and the technical areas and recommends the increase in reading informational texts be completed in these classes. One of the technical areas content area classes could be a culinary arts class, a marketing class, or a health science class, but consider this particular informational text as scrumptious for any class.

In organizing this story, New York Times reporter Michael Moss, who also narrates the embedded video, interviewed food scientist Steven A. Witherly, author of “Why Humans Like Junk Food,” in order to better understand how all of the chemical elements combine in the Nacho Cheese Doritos chip to make it alluring to our taste buds. According to Witherly, the mixing of flavors on this particular chip is purposeful:

“What these are trying to do is excite every stinking taste bud receptor you have in your mouth.”

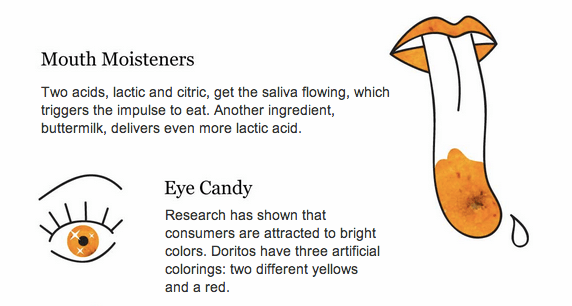

The graphics for the article by Alicia DeSantis and Jennifer Daniel are cleverly combined with photographs by Fred R. Conrad, also from the The New York Times. A separate page layout with the graphic/photo mix delivers tidbits of information about the Dorito chip. Each detail is organized by topic, as this example shows:

A teacher does not even have to work at organizing questions for students to answer since the New York Time Learning Network, a free educational blog offered by the paper, organized an entire lesson plan on this article. The lesson is titled 6 Q’s About the News | The Science Behind Your Craving for Doritos, organized by Katherine Schulten. The questions on the blog include:

WHAT is psychobiology?

WHAT is “dynamic contrast”?

HOW do the acids in Doritos work on the brain?WHAT is “sensory-specific satiety”?

WHERE do half the calories in Doritos come from, and, according to the graphic, HOW does that work on the brain?

WHY is “forgettable flavor” so important to Doritos’ success?

The higher order questions invite students to consider:

Now that you know the formula behind Doritos, are you more likely to eat more or less of them? WHY?

HOW many processed foods do you eat a day?

WHAT might a graphic explaining the effects of this food look like?

So go ahead. Read the Nacho Cheese Doritos article. See how irresistible an informational text can be. Once you read one this good, you will be searching to find another!