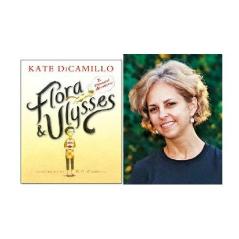

Kate DiCamillo stood in the nave of Riverside Cathedral, her curly hair barely visible over the podium, her voice clear and strong as she delivered the keynote address for the 85th Teacher’s College Reading and Writing Project Reunion (October 19, 2013).

She was exactly as advertised from the information on her website, “I am short. And loud.”

She addressed the packed house of literacy teachers, some 2000 strong, who knew her as the author of Because of Winn-Dixie (a Newbery Honor book), The Tiger Rising (a National Book Award finalist), and The Tale of Despereaux (winner of the 2003 Newbery Medal), but her morning speech was about her latest book, Flora and Ulysses. She set the stage with her opening proclamation:

She addressed the packed house of literacy teachers, some 2000 strong, who knew her as the author of Because of Winn-Dixie (a Newbery Honor book), The Tiger Rising (a National Book Award finalist), and The Tale of Despereaux (winner of the 2003 Newbery Medal), but her morning speech was about her latest book, Flora and Ulysses. She set the stage with her opening proclamation:

“This story begins as stories often do with a vacuum cleaner.”

Not just any vacuum cleaner. The vacuum at the center of this story was a 1952 tank Electrolux 2000, a treasured appliance belonging to DiCamillo’s mother. How treasured? DiCamillo joked that when her mother who was ill moved to be with her in Minneapolis, Minnesota, she worried more about the safe delivery of the Electrolux to the new home more than her own personal safety.”I want you to know that you can have the Electrolux when I am gone,” her mother told her. “It’s a really good vacuum cleaner,” she said and added, “The cord is extra long…and its retractable.”

The audience of teachers laughed; DiCamillo’s dry delivery in describing her mother’s attachment to a housecleaning appliance was part retrospective for the older teachers and part kitsch for the newer ones. “Remember the Hoover?” DiCamillo quoted her mother as saying, “that Hoover was useless!” But as she recounted how her mother’s illness progressed, the appreciation for this appliance took on new significance. “I really hope you will take the Electrolux,” her mother told her, “that makes me feel better.” So when her mother passed way, DiCamillo did take the Electrolux, but put it in the garage through that winter.

She spoke how in those dark days after her mother’s death, she found comfort in a poem by Rainer Maria Rilke, from Rilke’s Book of Hours: Love Poems to God and she read the lines from the short poem:

“God speaks to each of us as he makes us,

then walks with us silently out of the night.

These are the words we dimly hear:You, sent out beyond your recall,

go to the limits of your longing.

Embody me.Flare up like a flame

and make big shadows I can move in.

Let everything happen to you: beauty and terror.

Just keep going. No feeling is final.

Don’t let yourself lose me.Nearby is the country they call Life.

You will know it by its seriousness.Give me your hand.”

She reflected that when her mother was dying, she had held her mother’s hand in comfort, an action profoundly different from all the ways her mother had taken her hand when she was younger. The crowd was visibly moved by this retelling of the loss of her mother, but in typical DiCamillo storytelling fashion, her speech then veered off to include the death of a squirrel.

Shifting from the pathos for her mother, DiCamillo recounted that one day, a dying squirrel had chosen the front steps of her home as the last stop on his final journey. His eyes were open, yet unseeing; his chest dramatically heaving with his last breaths.

“I didn’t want him to suffer and die on my front steps,” she bemoaned.

So, she called a friend.

“‘There’s a squirrel on my front steps…He’s dying’,” she told her friend (Carla), “‘what should I do?'”

The advice she received from her gentle and humane friend appalled her.

“‘Do you have a shovel…and a tee shirt?'” asked Carla.

DiCamillo admitted that she had a shovel, but that she “moved away from the front door so the squirrel would not hear what was being said.”

“‘Put the tee shirt over the squirrel, and I will come over and hit him with the shovel,’ replied Carla.”

Fortunately, before that plan could be executed, the squirrel had crawled away.

“He may have heard us, or he had moved to get away from my presence,” said DiCamillo. The same people who had been tearing up from from the death of her mother and the power of the Rilke poem were now laughing out loud; the cathartic shift in emotions had been seamless.

DiCamillo then told the audience that she considered her reaction to the dying squirrel was not unlike the reaction of E.B.White in an essay he published in The Atlantic, “The Death of a Pig”:

“He came out of the house to die. When I went down, before going to bed, he lay stretched in the yard a few feet from the door. I knelt, saw that he was dead, and left him there: his face had a mild look, expressive neither of deep peace nor of deep suffering, although I think he had suffered a good deal. I went back up to the house and to bed, and cried internally – deep hemorrhagic intears.”

“White claimed that his novel Charlotte’s Web was not connected to this essay…but could this event,” DiCamillo speculated, “have been more?”

She paused to consider their mutual despair over loss.

“He wanted to keep the pig alive….I wanted to keep the squirrel alive.”

And in that instant, a cathedral full of teachers understood that great ideas do not happen in (pardon the pun) a vacuum. DiCamillo’s speech illustrated how the three seemingly unconnected elements in her keynote address were the elements of story she combined in her latest book Flora and Ulysses.

In this story, there is a vacuum, a squirrel, a shovel, and several lines of the Rilke poem.

To be more specific, there is the near death experience of the squirrel, mistakenly sucked up by the Ulysses 2000; there is a comic-book superhero aficionado who intervenes; and there are several drafts of meta-physical squirrel poetry. The story has the “beauty and terror” from the Rilke poem as well as the giving of a hand for comfort. There are what DiCamillo terms, “eccentric, endearing characters” presented in a format that combines print with comic book styled illustrations. Like the keynote address, the novel plucks at both the heart and the funny bone; it is a wonderful story.

The biography on DiCamillo’s website reads, “I write for both children and adults, and I like to think of myself as a storyteller.” Listening to her speak, I cannot think of her as anything else.

I was surprised that the play was paired with Of Poseidon, a romantic fantasy involving a independent and beautiful Emma and her strange encounters with the incredibly handsome Gaylen. I would have paired this book with Romeo and Juliet because the inferences about clan conflicts are too frequent not to imagine “two houses both alike in dignity, in the fair ocean where we lay our scene.” This debut novel by Anna Banks addresses mermaid lore, the legend of Atlantis, and forbidden love on the Jersey Shore. Unlike the TV show, listeners are 75% into the book before the first kiss; there is a great deal of “raising her chin with his fingers” and “cheek-stroking” to keep romantics hopeful. The reader (Rebecca Gibel) was also excellent, lacing some of the more exclamatory phrases with the right amounts of sarcasm or ruefulness. My only complaint was that this novel is the first in a series. As I got closer to the end of the recording, I began to realize that this novel was the “introductory”, a sentiment seconded by this reviewer:

I was surprised that the play was paired with Of Poseidon, a romantic fantasy involving a independent and beautiful Emma and her strange encounters with the incredibly handsome Gaylen. I would have paired this book with Romeo and Juliet because the inferences about clan conflicts are too frequent not to imagine “two houses both alike in dignity, in the fair ocean where we lay our scene.” This debut novel by Anna Banks addresses mermaid lore, the legend of Atlantis, and forbidden love on the Jersey Shore. Unlike the TV show, listeners are 75% into the book before the first kiss; there is a great deal of “raising her chin with his fingers” and “cheek-stroking” to keep romantics hopeful. The reader (Rebecca Gibel) was also excellent, lacing some of the more exclamatory phrases with the right amounts of sarcasm or ruefulness. My only complaint was that this novel is the first in a series. As I got closer to the end of the recording, I began to realize that this novel was the “introductory”, a sentiment seconded by this reviewer: