Mother’s Day is coming! There will be tributes and flowers and cards and perfume and candy and breakfasts, brunches, suppers, dinners given in honor of mothers. The phone networks will run white hot with continental and international calls with phone calls to mom.

I too will send flowers, and I will make a phone call, but I have already given her a little tribute in person this past month. Mom lives in Idaho, and I spent spring break with her and other members of my (large) family. We had lunch, I cooked dinners, and we did a little shopping. At night we would sit at the dining table and talk. Since April is poetry month, I decided to share one of my favorite poets, Billy Collins.

I found Billy Collins back in 2004 when he contacted teachers to participate in the Poetry 180 project, a poem a day for students in schools to be shared during daily announcements or posted on bulletin boards. Collins believes:

“Poems can inspire and make us think about what it means to be a member of the human race. By just spending a few minutes reading a poem each day, new worlds can be revealed.”

Just the thought of sharing a Billy Collins poem makes me start to grin. His verse is so wise and often very funny. The added benefit is that there are plenty of recordings of him reading his poems. His dead pan delivery of his poetry is priceless. Even hearing him give the explanation for a poem’s genesis makes me start to chuckle; on the video below, you can hear the audience do the same.

Collins introduces the poem The Lanyard by downplaying his efforts. “I did what most poets tend to do,” he notes in the opening explanation, “which is write about a topic that is rather large, to choose an image as a point of entry rather than take on the topic in a frontal way.”

That is an understatement since in this poem, the topic is large: “How can you repay your mother?”

The Lanyard – Billy Collins

The other day I was ricocheting slowly

off the blue walls of this room,

moving as if underwater from typewriter to piano,

from bookshelf to an envelope lying on the floor,

when I found myself in the L section of the dictionary

where my eyes fell upon the word lanyard.

No cookie nibbled by a French novelist

could send one into the past more suddenly—

a past where I sat at a workbench at a camp

by a deep Adirondack lake

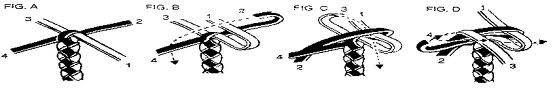

learning how to braid long thin plastic strips

into a lanyard, a gift for my mother.

I had never seen anyone use a lanyard

or wear one, if that’s what you did with them,

but that did not keep me from crossing

strand over strand again and again

until I had made a boxy

red and white lanyard for my mother.

She gave me life and milk from her breasts,

and I gave her a lanyard.

She nursed me in many a sick room,

lifted spoons of medicine to my lips,

laid cold face-cloths on my forehead,

and then led me out into the airy light

and taught me to walk and swim,

and I, in turn, presented her with a lanyard.

Here are thousands of meals, she said,

and here is clothing and a good education.

And here is your lanyard, I replied,

which I made with a little help from a counselor.

Here is a breathing body and a beating heart,

strong legs, bones and teeth,

and two clear eyes to read the world, she whispered,

and here, I said, is the lanyard I made at camp.

And here, I wish to say to her now,

is a smaller gift—not the worn truth

that you can never repay your mother,

but the rueful admission that when she took

the two-tone lanyard from my hand,

I was as sure as a boy could be

that this useless, worthless thing I wove

out of boredom would be enough to make us even.

from The Trouble with Poetry. Purchase from Amazon (here).

Like the speaker in the poem, I have given my mother a lanyard I made during day camp. I also have given her a pile of acrylic woven potholders that could not possibly protect a hand against the heat of a pan, several cigarette ashtrays when no one in our immediate family smoked, a plethora of pasta strung on elastic cords that she could wear around her neck, and several tile trivets that left specks of powdery plaster of Paris on the dining table when it was brought out only for special occasions. I understand Billy Collin’s taste in art.

I also understand that I can never repay my mother. I find that hard to communicate to her directly, and so I too have to take on the large topic of a mother’s love with smaller points of entry. I cleaned out the spice rack, consolidating jars and removing a can of mace spice from the A & P that had travelled West with her some 30 years earlier. We found letters, some written by my father or to my father who passed away 23 years ago; we listened to my brother read the letters aloud and remembered how well my father had cared for all of us. We sat in the sun, and we marveled at her view of the city of Boise on a clear spring afternoon. And I shared Billy Collin’s poem, “The Lanyard” knowing full well that nothing could ever make us even.