I am sitting through a professional development session on how to use peer to peer writing conferences. I want to believe there will be a moment in this workshop when the “ah-ha” moment will happen, when I finally unlock the formula for successful in class peer to peer writing conferences at the high school level. The presenter reiterates how important this process is for writers to hear critical feedback to their writing. I hear again that “sticking with it and training students” to peer to peer conference are key ingredients that will improve student writing. Then I think of my students….my 9th, 10th and 11th grade students. This unspoken heresy forms in my mind:

Forgive me, well-intended and passionate presenter, but in my experience, in class peer to peer writing conferences do not work.

There, I admit it. Success in implementing face to face, peer to peer writing conferences, real critical encounters, has eluded me. I have 20 plus years in the English classroom, grades 6-12, and I have always come away from peer to peer writing conference sessions with the uncomfortable opinion that I have been wasting class time.

There, I admit it. Success in implementing face to face, peer to peer writing conferences, real critical encounters, has eluded me. I have 20 plus years in the English classroom, grades 6-12, and I have always come away from peer to peer writing conference sessions with the uncomfortable opinion that I have been wasting class time.

I now know why.

This summer, I am participating in the Connecticut Writing Project, and I have to write on demand, and then I must share that work. This is a horrible experience for me. I pass my paper wondering, “What will this person think of me?” and “What if there is a grammar error? I’m an English teacher!!” I have to provide feedback on a fellow teacher’s work, and I see the same kind of panic in her eyes.

I quickly reflect. How does my adolescent, pimply, over-stimulated teen-age boy feel as he hands in his rough draft for a critique by the fair skinned, sweet smelling young girl who sits behind him? How does that painfully shy artist who doodles his responses but has yet to complete a paragraph in writing feel about sharing his work with the amazingly popular class jock (boy or girl)?

I mention this to the presenter who says, “Yes, sometimes, there are student combinations that do not work.” That confirms my problem.

Problem #1: My struggle with peer to peer conferencing begins with setting up partnerships. Do I put the uneven writer with the good writer? Does the good writer need another good writer for good editing? Do I put two poor writers together and expect a miracle? Do I let the students choose their partners? How effective is the conference if friendship is in play?

Problem #2: The research shows that students should learn how to peer conference in the elementary and middle school grades to carry that behavior into the high school grades.However, I have found that training in writing conferences in the elementary and middle school grades is erased in the high school environment. Many high school students claim to hate sharing their work with other members of the class; participation is mixed.

Problem #3: I teach in a regional school where one third of our freshman class comes from out of district schools. Several of these students have not had any training in peer conferencing. The number of incoming students who are already uncomfortable in moving to a new regional school requires that I need to start at square one and train everyone how to conference effectively.

Ultimately, I do not want to give up on students providing critical feedback to other student; I just want to take away the awkward immediacy of that face to face encounter. Since I teach in a 1:1 school district with digital literacy embedded in my curriculum, I will continue to use the solutions that have worked in place of those face to face, peer to peer writing conferences. I use digital conferencing.

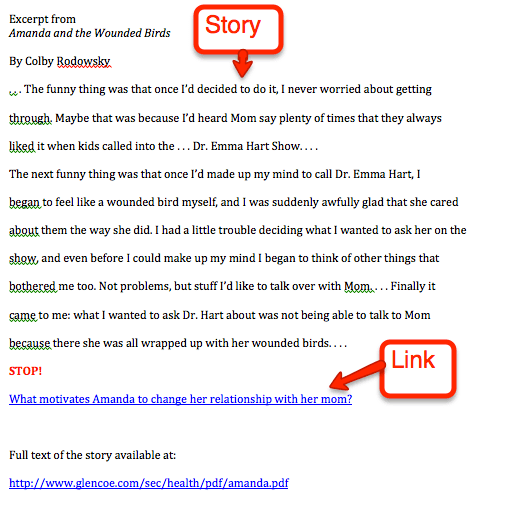

Solution #1: I use blogs. Each blog is organized for a small group (8-10 students) to use as a team. Only members of their team see their posts and comments over a period of time, say a semester or a school year. Students post book reviews, and other students comment on that post by asking questions about the book, or by making recommendations to improve the original book review post. Each student must respond to the posted book reviews. Writing on the blogs allow students the physical distance they need to comfortably respond to each other. Written comments take time to construct, and students are more thoughtful if they know what they write will have a larger audience. Blogs let me monitor the comments as well and determine which students are the most effective in providing good critical feedback to a student and which students are simply putting down, “great job!” or “I like what you wrote!” I might not have this information if the students were having face to face conferences. During my writing conferences with students I can follow up with the comment stream and target what is necessary to improve a critical response.

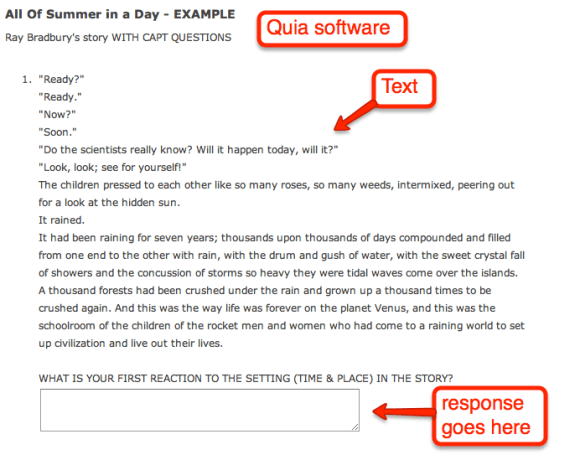

Solution #2: I use wikis. Students upload a report or story to a wiki page, and their peers can respond with questions and provide feedback in the comment section at the bottom of the digital page. Here too, the wiki page and the comment section will be seen by a larger audience and students are more thoughtful if they know their work will be read by an entire class. Responses in the comment section of the wiki also allows me to monitor who has provided good critical feedback to the writer.

Solution #3: I use Google docs. Students can upload their work to a Google doc and share that link with one or more students. Each peer reviewer can use the comment feature to provide feedback. This feature also identifies the peer conference partner on each comment he or she makes.  All comments by the peer reviewer are recorded on the document’s margin. An student author can even post questions about his or her writing in a comment box. The document can be also shared with multiple students who could work on the same document at the same time if necessary. All comments are part of the document’s history, and I can monitor changes made by the student writer before and after a peer review. This method is particularly helpful if I have specific students who are hesitant about facing another student in a peer review.

All comments by the peer reviewer are recorded on the document’s margin. An student author can even post questions about his or her writing in a comment box. The document can be also shared with multiple students who could work on the same document at the same time if necessary. All comments are part of the document’s history, and I can monitor changes made by the student writer before and after a peer review. This method is particularly helpful if I have specific students who are hesitant about facing another student in a peer review.

Of course, all this digital peer to peer conferencing is improved if I provide students with guiding questions (“Did the opening engage you as a reader?”) they would use in written conferences or if they prepare specific questions for the peer reviewer.

Digital platforms: wikis, blogs, and Google docs, allow me the means to provide peer to peer writing conferences by removing those awkward face to face conferences that I have found so unproductive in my high school classrooms. These digital platforms also let me organize students across class periods, and if I found a teacher in a cooperating school who wanted to peer conference, the digital platforms would allow my students to conference outside the classroom. Students still have plenty of opportunities for face to face encounters during class discussions and presentations, but they are comfortable communicating their feedback about a peer’s writing in a digital environment. And, heresy or not, I am finally comfortable with the productive peer to peer (via the Internet) writing conference.