The amazing artwork in the hallways of the middle school was created by….(wait for it)…math classes!

Last week, Ms. Nihan, the 8th math teacher posted drawings created by students who were studying a geometrical pattern based on the work of a 5th Century Greek mathematician, Theodorous of Cyrene. He developed a pattern called the Spiral of Theodorous, a square root spiral composed of contiguous right triangles.

The artwork on the walls represents a Common Core Mathematical Standard:

CCSS.Math.Practice.MP7 Look for and make use of structure.

“Mathematically proficient students look closely to discern a pattern or structure.” This standard can also represent poetry patterns. Rhythm, rhyme scheme, repetition are all part of poetic patterns and structure that proficient students in English should use in close reading.

Therefore, a tribute to a few of student drawings is in order; each is matched with a poem with a distinct pattern.

First up, a “lullaby” with a rhyme scheme and refrain pattern (a-a-a-refrain-b-b-b-refrain). Like “Rock a Bye Baby”, this poem is more frightening than comforting, as the narrator clearly plans to place the child in a hazardous area!

Lullaby

Samuel Hoffenstein (1890-1947)

Yes, I’ll take you to the zoo,

To see the yak, the bear, the gnu,

And that’s the place where I’ll leave you–

Sleep, little baby!

You’ll see the lion in a rage,

The rhino, none the worse for age;

You’ll see the inside of a cage–

Sleep, little baby!

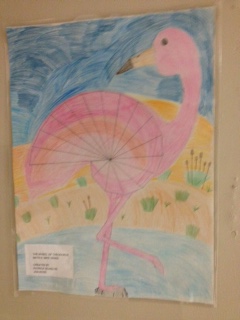

Next up, a quick tribute to the flamingo. This is an offering with the pattern of iambic tetrameter and a single rhyme (glum/gum).

The Flamingo Poem

Richard Medrington

Flamingos dress in fetching pink

can be rather glum,Their legs being made of plastic tubes

And bits of chewing gum.from An Absird Book of Burds (Edinburgh: Puppet State, 2003)

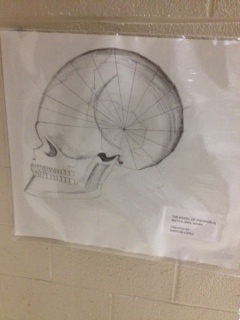

The next poem is a humorous offering titled “X-ray” with two quatrains, each containing one rhyme (Jones/bones; sight/night):

X-Ray

by Joan Horton

“This is your x-ray,”

Said young Doctor Jones.

As he held up a picture

And showed me my bones.

(continued here)

In making these extraordinary drawings, students had to follow a specific pattern for the Spiral of Theodorus:

The spiral is started with an isosceles right triangle, with each leg having unit length. Another right triangle is formed, an automedian right triangle with one leg being the hypotenuse of the prior (with length √2) and the other leg having length of 1; the length of the hypotenuse of this second triangle is √3. The process then repeats; the ith triangle in the sequence is a right triangle with side lengths √i and 1, and with hypotenuse √i + 1.

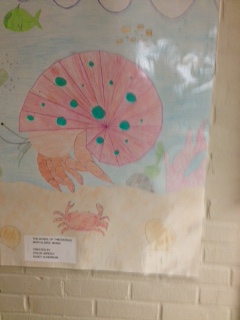

The original rendering by Theodorus is remarkably like a seashell, so here is an Amy Lowell poem matched with a seashell and its inhabitant, a small hermit crab. This poem has similarities to a Sonnetina Due-a 10 line poem with rhyming couplets. The poem also has a repeated “sing-song” line “Sea Shell, Sea Shell“:

Sea Shell

Amy Lowell

Sea Shell, Sea Shell,

Sing me a song, O Please!

A song of ships, and sailor men,

And parrots, and tropical trees,

Of islands lost in the Spanish Main

Which no man ever may find again,

Of fishes and corals under the waves,

And seahorses stabled in great green caves.

Sea Shell, Sea Shell,

Sing of the things you know so well.

Some of the other drawings are seen here:

Patterns in math meet patterns in poetry, and I am happy to report that no square roots were harmed in this enterprise…Thanks to Ms. Nihan and the 8th grade practitioners of patterns!