I hear the chatter from elementary school teachers:

- They can’t wait for reading!

- Oh, they love to read!

- When we have to cancel reading, they are so disappointed.

Yet, what happens when I get the ninth graders in my class? I hear:

- Reading is so boring.

- I hate to read.

- I don’t like reading.

What caused the change in students’ attitude towards reading?

Reading Speed Limit?

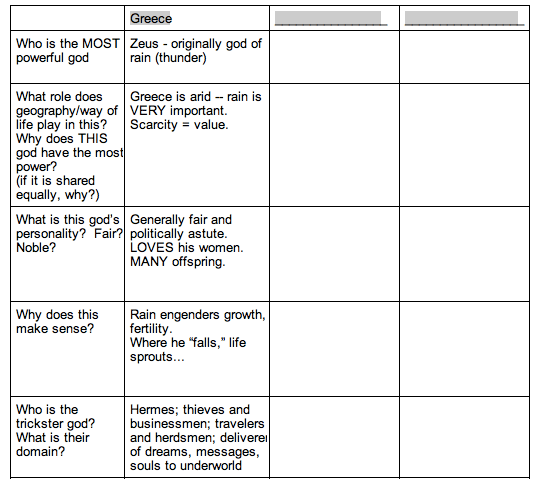

I have been attending graduate courses on reading instruction for pre-K-6 in order to find out the reason for the shift in attitudes. One of the textbooks used was Guiding Readers and Writers (Grades 3-6), a 672 page tome packed with information written by authors Irene Fountas and Gay Su Pinnell. The 2001 edition reflected the ideal reading and writing workshop schedule; 3.5 hours of uninterrupted reading and writing daily.So, how did the instructional strategies for elementary students in the Fountas and Pinnell book prepare students for grades 7-12 ?

The Fountas and Pinnell strategies use a Benchmark Assessment System that allowed for leveled literacy intervention for very early readers. Texts were rated (A to K) on their difficulty for the reader in fluency and comprehension at instructional or independent levels. Each level suggests a percentage of accuracy that a student should achieve before moving to the next level, for example:

For levels A to K, a text read at 90%-94% accuracy (with satisfactory or excellent comprehension) is considered an instructional level text. That means that the student can read it effectively with teacher help–a good introduction, prompting, and discussion).

For levels A to K, a text read at 95%-100% accuracy (with satisfactory or excellent comprehension) is considered to be an independent level text. That means that the student can read it without help. Reading at the independent level is extremely valuable because the reader gains fluency, reading “mileage,” new vocabulary, and experience thinking about what texts mean (comprehension).

Fountas and Pinnel are very clear that these percentages should not be fixed, stating:

We wouldn’t want anyone to interpret these percentages in a rigid way, of course. A child might read one text at 91% and then experience a few tricky words in the next book and read it with 89%.

They also note that reading broadly increases a student’s vocabulary, and they suggest that schools could mandate their own policies in insuring that students reading smoothly and easily with satisfactory accuracy and comprehension before moving to the next level.

I heard, however, a number of literacy specialists/instructors from elementary schools in my classes representing different districts in the state explaining, “We hold students to a 97% accuracy rate before moving them on” or “I would not move a student who isn’t reading at a 95%-97% accuracy rate.” Are these literacy specialists/instructors misreading the Fountas and Pinnell book? Furthermore, is a district’s adherence to this 97% accuracy rule hurting students as they transition to the higher grade levels? If a student is directed to read only those books that can be read at 97% or even a 91% or 89% accuracy, what happens when he or she is handed a required text that is above his or her reading level?

The problems in reading accuracy are clearly evident in when students enter middle school, and they are handed textbooks and whole class novels from the literary canon. Richard Allington, a past president of the International Reading Association and the National Reading Conference, wrote an article that directly addressed the problem of difficult texts for the journal Voices from the Middle (May 2007, NCTE) titled, “Intervention All Day Long: New Hope for Struggling Readers “ In this article, Allington makes the argument that districts should not mandate the same grade level texts for readers of varying ability:

This means that districts cannot continue to rely on one-size-fits-all curriculum plans and a single-period, daily supplemental intervention to accelerate struggling readers’ academic development. Districts cannot simply purchase grade-level sets of materials—literature anthologies, science books, social studies books—and hope to accelerate the academic development of students who struggle with schooling. There is no scientific evi- dence that distributing 25 copies of a grade-level text to all students will result in anything other than many students being left behind.

He argues for an extension of the 97% accuracy rate using easier texts and explains that the more difficult texts at the middle and high school levels will have many more words per page than the texts in elementary school. He notes that in a book of 250 and 300 running words on each page, 97% accuracy would mean 7–9 words will be misread or unreadable on every page:

In a 20-page chapter, the student would encounter 140–180 words he or she cannot read. And typical middle school textbooks have twice as many words per page, creating the possibility that a reader reading at 97% accuracy would be unable to correctly read 14–20 words per page or 250–400 words per chapter.

As a result, Allington argues that struggling readers will not be helped by reading these texts, regardless as to the amount of support.

The very texts that are supposed to be a resource for a discipline’s content, “won’t help them learn to read.” Many upper grade level texts are textbooks are heavy, difficult to read with all the subject specific vocabulary embedded in passages; the different fonts, pictures, and information boxes may confuse a poor reader.

I am, however, a little skeptical about Allington’s point regarding students who miss words in texts. I am not sure that the multiplication factor Allington uses to calculate the number of words missed since words are repeated in a novel. Yes, a student may miss “purloined” on page 12, and on page 17, but should that word be counted twice? There is a context that eventually brings about an understanding; by the third “purloined” a student may have a better understanding of the word because of that context. As an additional concern, requiring a 97% accuracy rate would stop most middle/high school literature programs that use whole class texts. For example, we teach Romeo and Juliet to our 9th graders, and the accuracy rate for Shakespeare, even for teachers with Master degrees in English, is about 80%. Yet, year after year, as we read the play aloud, students do understand generally what is going on. Perhaps some literature is as the poet T.S. Eliot wrote, “Poetry communicates before it is understood.”

On the other hand, Allington has every reason to be concerned that students entering middle school and high school will encounter texts that are complex with high exile levels. These texts will not be modified to accommodate struggling readers, instead the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) are moving in the opposite direction with Lexile levels being raised at all grade levels. Allington’s concerns are not the concerns for publishers who want to meet the CCSS in order to sell as many textbooks as possible. Ultimately, a 97% accuracy rate is not realistic with the materials in each subject area at the middle school and high school levels.

The students who have been swimming in the shallow end of the reading pool throughout their elementary school experience are suddenly tossed into the deep end of literature and informational texts when they hit middle school. The aforementioned elementary literacy specialists/instructor’s adherence to the 97% accuracy with Fountas and Pinnell benchmark assessments limit students to highly filtered reading experiences as opposed to challenging students to develop their own strategies when they encounter difficult texts. More practice with difficult reading materials should be part of an elementary school literacy regimen, just like a batter at the plate who must learn how to swing at a number of different kinds of pitches; not every pitch comes in the strike zone over the plate, and not every book is at a prescribed accuracy rate.

Requiring every student read at a 97% accuracy rate was not the intention of the Fountas and Pinnell directives, but the directives of others may be contributing to the comments I hear from my grade 9 students that “Reading is so boring” or “I hate to read.” A steady diet of the same level of reading caused by requirements to achieve a 97% (or A+) accuracy may hem in or deaden a student’s independent nature or curiosity. Furthermore, when a student gets to middle school, the requirement to read at 97%, or any literacy rate, is not enforced in all disciplines; students who have been spoon-fed reading materials may feel betrayed. Their 97% or A+ reading excellence is suddenly plunged to lower percentiles, which ultimately results in much lower grades. Any confidence or trust a struggling reader may have developed with purified texts is quickly lost, and “I hate to read” is the result.

Maybe they don’t hate to read; maybe with years of preparation at 97%, they are unprepared for any other speed.

Students are more creative than Coleman recognizes in his untested design of the CCSS. From the beginning of their academic careers, they draw their metaphors: smiling suns, hearts in hands, trees with large red dots. They start simply “Freddie is a pig when he eats,” before moving to more sophisticated constructs on their own such as “Love is a chocolate fountain that never runs out.” They are capable of sustaining elaborate metaphors to explain the writing process:

Students are more creative than Coleman recognizes in his untested design of the CCSS. From the beginning of their academic careers, they draw their metaphors: smiling suns, hearts in hands, trees with large red dots. They start simply “Freddie is a pig when he eats,” before moving to more sophisticated constructs on their own such as “Love is a chocolate fountain that never runs out.” They are capable of sustaining elaborate metaphors to explain the writing process: