Today is Digital Learning Day! To mark the occasion, let me take you through a quick walkthrough of the halls of Wamogo Regional Middle/High School and give you a snapshot on how digital learning looks in the English classrooms grades 7-12. We have 1:1 computers in grades 7 & 8; in grades 9-12, we have a “bring your own digital device” policy. Here are the digital learning activities on Wednesday, February 6, 2013:

Grade 7: Students responded to a short story they read, “The Amigo Brothers”. They accessed the wiki (www.PBworks.com) in order to respond to “close reading” questions on the author’s use of figurative language. (Students are required to use evidence in their responses; digital copies of text helps student correctly add and cite evidence).

Grade 8: Students uploaded their reviews of the books (Mississippi Trial, 1955; Chains; The Greatest) they have been reading in literature circles to www.edmodo.com. These reviews are connected to the Common Core Writing Standard #6:

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.8.6 Use technology, including the Internet, to produce and publish writing and present the relationships between information and ideas efficiently as well as to interact and collaborate with others.

Grade 9: Students responded to a “writing on demand” journal prompt in preparation for the novel Of Mice and Men. This prompt is connected to the theme of hopes and dreams, and the students were asked:

What is your hope for life, your goal, or even your dream? What do you think you want from the future? What would you live without, dream-wise? What couldn’t you live without?

The students also posted their responses on a www.Edmodo.com discussion thread. Selections from responses included:

- Something I couldn’t live with out would be my grandparents because they are like another set of parent to me, just better. They mean so much to me, that I really couldn’t see my life without them.

- I hope to be a plant geneticist in the future, that is my hope but no matter what happens I would like to have a career involving plants and even if I can’t get a career in genetics I know it will always be a hobby of mine.

- My house will be by the ocean, so close I can see it out of my kitchen window. I will grow old and drink coffee on my porch, while I read the paper and wave to my neighbors who walk by!

- I could live without being famous around the world but I would like to be known town wise. I cannot live without family and their support in my decisions. They help me to stay confident and get through whatever I want to accomplish in life.

- I think I could live without wanting a huge house or a huge boat “dream-wise”, but that still doesn’t mean I don’t want those things. I couldn’t live without music or my family.

- My biggest hope and dream is to have a really big plot of land and have the world’s biggest tractor and a bunch of snowmobiles and ATV’s.

- I want to be able to adopt kids from Uganda but also have my own, and I want to live in a nice house with a big yard. I want to work with little kids as a job.

10th grade Honors English students are reading Great Expectations. They took a quiz on www.quia.com, a software platform for timed quizzes. The College Prep English classes are reading Animal Farm. Today, they had to access “The International” MP3 and the www.youtube.video of the Beatle’s song “Revolution.

For homework tonight, students will write their own “protest” song.

Grade 11: Students can access the vocabulary list from the film The Great Debaters through the class wiki (www.pbworks.com) while the Advanced Placement English Language students watched a YouTube video of a Langston Hughes poem “I, Too, Sing America” read by Denzel Washington:

They prepared responses to the following questions which were posted on the class wiki:

- To whom is the poet writing? How do you know?

- Choose one stanza and discuss what you feel is the key word in this stanza and explain why you chose this word?

- What feelings does the poem create? Which words create this feeling?

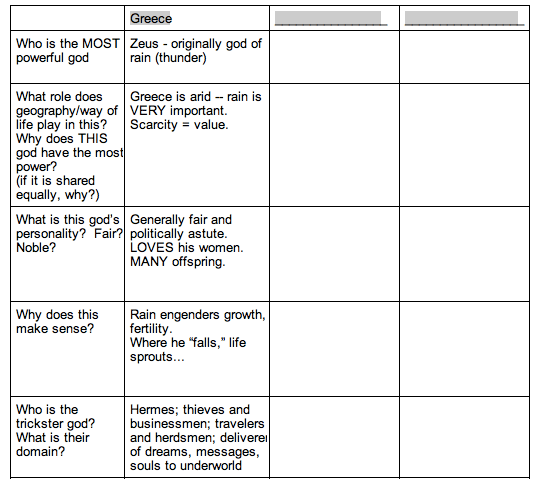

Grade 12: Students in the Grade 12 Mythology class accessed the following Google Doc Template and filled in the chart with their own research about the mythologies of different cultures. This activity meets the CCSS writing:

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.11-12.7 Conduct short research projects to answer a question; narrow or broaden the inquiry when appropriate; synthesize multiple sources on the subject

The Film and Literature class “flips” the content by having students watch films for homework in order to discuss them during class. Tonight’s assignment? Watch the following YouTube clip and be ready for an open note quiz:

Students in the Advanced Placement English Literature class read the short story “Barn Burning” by William Faulkner that was embedded with a quiz on www.quia.com. They then created a list of four themes from the short story on a Google Doc. Each student selected a theme and placed his/her responses in the Google Drive folder to share with other members of the class. Examples included:

- Actions we take with the grotesque: Shun? Avoid?

This story embodies an ultimate grotesque atmosphere. Even Colonel Satorius Snopes’ sisters are described as, “hulking sisters in their Sunday dresses” (2). These sisters are emulated throughout the story as disgusting, rotund, lethargic, and hog-like beings. This grotesque physical trait emulates the family’s condition in society. Satorius’ clothes are described as, “patched and faded jeans even too small for him.” (1).

- Family over law or law over family

For the boy to go against his family in the end further proves his actions of courage and strength, and portrays the theme of law over family. “Then he began to struggle. His mother caught him in both arms, he jerking and wrenching at them. He would be stronger in the end, he knew that. But he had no time to wait for it” (10). His whole family is holding him back, but he chooses to go against all of them and do what is right.

This quick walkthrough demonstrating the use of technology in the English classrooms on one day demonstrates that for the teachers and students at Wamogo, everyday is a Digital Learning Day!

The association of midterm exams with freezing is both literal (I teach in the Northeast) and figurative (many students “freeze up” during an exam), so at the end of this semester, I took one of the writing standards from the Common Core State Standards hoping at the very least to stop the “freeze” in the classroom during the exam. Instead of a multiple choice exam with essay questions, I prepared my 12th grade students to write an inquiry paper that would be due the morning of the exam. Yes, even those seniors who had repeatedly assured me that they will never go to college would be tasked with a three to five page paper academic paper that touched on the material that we had read over the course of the semester.

The association of midterm exams with freezing is both literal (I teach in the Northeast) and figurative (many students “freeze up” during an exam), so at the end of this semester, I took one of the writing standards from the Common Core State Standards hoping at the very least to stop the “freeze” in the classroom during the exam. Instead of a multiple choice exam with essay questions, I prepared my 12th grade students to write an inquiry paper that would be due the morning of the exam. Yes, even those seniors who had repeatedly assured me that they will never go to college would be tasked with a three to five page paper academic paper that touched on the material that we had read over the course of the semester.