Enter the spoiler alert. Because the number of ways people hear about stories is increasing, spoiler alerts for books and films are offered as a “heads-up”, a means to prevent plot details from becoming public. Knowing the end of a story might mean that the strategy of “predicting” a story has been compromised, however, there are genres of stories that absolutely count on predictability, for example, Nancy Drew will always solve a mystery with her best friend, Bess and George, while on TV, predictability has a time limit; the shipwrecked crew will never leave Gilligan’s Island (30 mins) and House will solve a medical mystery (60 mins).

Enter the spoiler alert. Because the number of ways people hear about stories is increasing, spoiler alerts for books and films are offered as a “heads-up”, a means to prevent plot details from becoming public. Knowing the end of a story might mean that the strategy of “predicting” a story has been compromised, however, there are genres of stories that absolutely count on predictability, for example, Nancy Drew will always solve a mystery with her best friend, Bess and George, while on TV, predictability has a time limit; the shipwrecked crew will never leave Gilligan’s Island (30 mins) and House will solve a medical mystery (60 mins).

Predictability means to state, tell about, or make known in advance, especially on the basis of special knowledge, and students are taught at an early age that making predictions can help them to determine what will happen in a story.

I noticed how predictions are important even if the end has already been decided when my six-year-old niece was watching the Disney film Running Brave. This was her favorite film, and she watched the VHS tape every afternoon. On one such afternoon, I noticed she was drifting asleep, so I made a move to turn off the video.

“Wait,” she cried out, “I think….I think he’s going to win again.”

From her perspective, the outcome of the race was still in doubt. The cinematic elements, the tight editing of shots , and a triumphant soundtrack created suspense where the viewer might doubt the inevitable. Krista had seen the movie hundreds of times, but she still was “testing” her prediction.

I admit that I have felt the same way watching Miracle, holding my breath for the final seconds wondering if the US ice hockey team would still win the Olympic medal. Krista’s experience is also mirrored in the classes where students often choose books based on a movie that they have seen.

In the independent reading allowed in our curriculum, the 9th graders can choose contemporary fiction or non-fiction, and many of the titles have movies in circulation, for example:

Some students purposefully choose these books because they know the endings, and in knowing how the book ends allows the reader to pay more attention to the craft of the author in bringing all the plot points together in a conclusion. Take for example, the Harry Potter series. Most readers predicted with certainty that Harry Potter would finally face his nemesis, Voldemort. The how and when, however, were still very much in the air, and J.K.Rowling’s crafting of the series’s magical settings and character development kept readers in a willing suspension of disbelief for the length of seven volumes. The final conclusion was satisfying to her fans who knew all along that Harry would prevail, after all, Good’s triumph over Evil is a predictable plot. Readers and filmgoers were not disappointed in following the story of a boy with the scar on his forehead because in each volume and subsequent film release, they correctly predicted that “I think…I think he will win again.”

So when I teach a whole class novel, I know there are some students who already know the ending. They may have reached the conclusion before others, or been informed by older students who notoriously share their opinions and critical information with younger students. In this case, my role is to impress on students that knowing the outcome will not destroy a well-told story, and to focus their attention on the other elements. This was the case with John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men.

“I heard this is a sad book,” one student said when I assigned the first chapter, “One guy kills another guy.”

Other students looked up for my confirmation.

“Yes, this is a sad book, but the reason for the sadness is really about caring. We will grow to care for these characters.”

“I already don’t care if I already know what happens,” was his reply.

Four weeks later, this student refused to watch the final scene in the film version.

“I know what happens, and I cannot watch,” he said sadly as he walked out into the hall.

The same sentiments are expressed at the beginning of our study of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet.

“Guess what? They die,” said a student as I passed out the books.

“Yes, they die,” I kept passing out the copies.

“So why are reading this?” another asked.

“Because this is a great story,” I responded, “and the story’s ending will mean more after we finish because we will have read how Shakespeare writes about these ‘star-cross’d lovers’.”

“But we already know how it ends!” they whined.

Now that we are in Act III, no one cares that they know the end, instead, they are recognizing how Shakespeare creates the tragedy. They notice the “hints”: Juliet seeing Romeo “As one dead in the bottom of a tomb”, Friar Lawrence’s herbs of “Violent delights”, and “Love devouring death”.

This discovery of an author’s details makes students more appreciative of the craft in writing as they still try to predict. They notice Shakespeare’s allusions: “Such a wagoner/As Phaeton would whip you to the west/And bring in cloudy night immediately” (3.2.2-4), because we had studied the Phaeton myth earlier in the year.

“Uh-oh. That’s not good,” I heard one say, “Romeo’s gonna crash and burn like Phaeton.”

That kind of analysis is exactly what the English Language Arts Common Core would like to see in a close reading of a text. How interesting that students who already know “what happens” may be better at picking up on an author’s craft that a close reading generates.

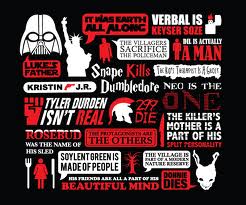

Spoiler alerts do warn those readers or viewers who want to be surprised, but knowing the ending does not necessarily ruin the reading or viewing experience. Want to experiment? Here are 50 plot spoilers for 50 novels. I predict that each novel will not disappoint, even if you already know the ending.