“We are not used to live with such bewildering uncertainty,” wrote Jessica Stern in a New York Times editorial How Terror Hardens Us on Sunday (12/6/15) after the San Bernardino, California, shootings.

Stern, an adult, was writing about adults collectively when she used the pronoun”we.”

That same bewildering uncertainty also confronts our children, our students in schools. That bewildering uncertainty is happening at a vulnerable time, just when they are just learning to be citizens in our democracy. That same state of terror, a state of intense fear, has an impact on their state of mind as each terrorist attack, Stern notes, “evokes a powerful sense of dread.”

Stern, a professor at Boston University’s Pardee School of Global Studies, co-authored ISIS: The State of Terror. She noted in her editorial:

“It [terrorism] is exactly that kind of psychological warfare that It is a form of psychological warfare whose goal is to bolster the morale of its supporters and demoralize and frighten its target audience — the victims and their communities. Terrorists aim to make us feel afraid, and to overreact in fear.”

Students in our classrooms today attend schools where terrorism or home-grown violence is a possibility; the term “lockdown” is part of their vocabulary. At every grade level, they have every reason to believe that they could be a target audience. while motives for violence have differed, many students are aware that high-profile incidents have happened in schools: Columbine (1999) and Sandy Hook (2012).

As educators in all disciplines at every grade level struggle to help students deal with recent events that are identified as terrorism, perhaps the discipline of social studies is the subject where educators can best counter a terrorist’s goal to have our students “afraid and overreact in fear.”

That academic responsibility to help students cope was claimed 14 years ago by the president of the National Council of Social Studies (NCSS) in 2001, months after the attacks on the Pentagon and the Twin Towers at the World Trade Center.

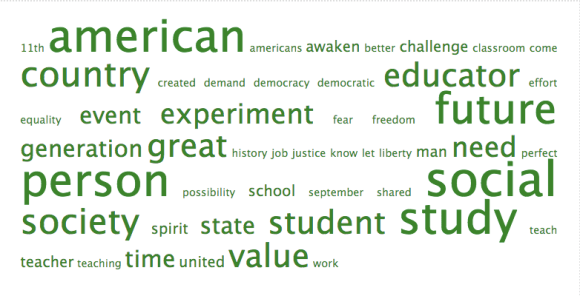

The most frequent words enlarged from the speech given by Aiden Davis, President of National Council of Social Studies after 9/11/2001 (www.wordsift.com)

When Adrian Davis delivered his 2001 NCSS Presidential Address to the nation’s social studies teachers, he explained their role as educators included efforts to “to work to reconstruct schools to become laboratories for democratic life” by saying:

“Schools do not exist in a vacuum. They are not isolated from their neighborhoods and communities. Schools and teaching reflect society, and they participate in constructing the future society.”

When Davis gave this address, he was making the case that terrorism had made the discipline of social studies more relevant to future societies than ever before. He anticipated that there would be people who could “overreact in fear”; his address hoped to point out that students would need guidance so that democracy would survive the bewildering uncertainty after 9/11:

As social studies educators, we need to reinforce the ideals of equality, equity, freedom, and justice against a backlash of antidemocratic sentiments and hostile divisions. As social studies educators, we need to teach our students not only how to understand and tolerate but also how to respect others who are different, how to cooperate with one another, and to work together for the common good.

Davis’s concerns about teaching respect and how to cooperate are even more important today when there is heated rhetoric conflating terrorism with religion. His reason to encourage social studies teachers to reinforce the ideals of equality, equity, freedom, and justice provides a solution to the concerns in Stern raised in her How Terror Hardens Us.

Stern’s editorial concludes, “If we are to prevail in the war on terrorism, we need to remember that the freedoms we aspire to come with great responsibilities.”

On behalf of all social studies educators, Davis accepted those responsibilities. As he concluded, he made clear the commitment he was making for teachers, “We have an opportunity to teach the coming generations to preserve and extend the United States as an experiment in building a democratic community….teaching is where we touch the future.”

The future is always uncertain, but educators, especially social studies educators, can provide students the skills of citizenship to deal with uncertainty so that they will not overreact in fear.