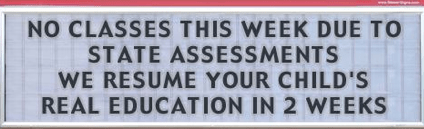

March in Connecticut brings two unpleasant realities: high winds and the state standardized tests. Specifically, the Connecticut Academic Performance Tests (CAPT) given to Grade 10th are in the subjects of math, social studies, sciences and English.

March in Connecticut brings two unpleasant realities: high winds and the state standardized tests. Specifically, the Connecticut Academic Performance Tests (CAPT) given to Grade 10th are in the subjects of math, social studies, sciences and English.

There are two tests in the English section of the CAPT to demonstrate student proficiency in reading. In one, students are given a published story of 2,000-3,000 words in length at a 10th-grade reading level. They have 70 minutes to read the story and draft four essay responses.

What is being tested is the student’s ability to comprehend, analyze, synthesize, and evaluate. While these goals are properly aligned to Bloom’s taxonomy, the entire enterprise smacks of intellectual dishonesty when “Response to Literature” is the title of this section of the test.

Literature is defined online as:

“imaginative or creative writing, especially of recognized artistic value: or writings in prose or verse; especially writings having excellence of form or expression and expressing ideas of permanent or universal interest.”

What the students read on the test is not literature. What they read is a story.

A story is defined as:

“an account of imaginary or real people and events told for entertainment.”

While the distinction may seem small at first, the students have a very difficult time responding to the last of the four questions asked in the test:

How successful was the author in creating a good piece of literature? Use examples from the story to explain your thinking.

The problem is that the students want to be honest.

I should be proud that the students recognize the difference. In Grades 9 & 10, they are fed a steady diet of great literature: The Odyssey, Of Mice and Men, Romeo and Juliet, All Quiet on the Western Front, Animal Farm, Oliver Twist. The students develop an understanding of characterization. They are able to tease out complex themes and identify “author’s craft”. We read the short stories “The Interlopers” by Saki, “The Sniper” by Liam O´Flaherty, or “All of Summer in a Day” by Ray Bradbury. We practice the CAPT good literature question with these works of literature. The students generally score well.

But when the students are asked to do the same for a CAPT story like the 2011 story “The Dog Formerly Known as Victor Maximilian Bonaparte Lincoln Rothbaum”, they are uncomfortable trying to find the same rich elements that make literature good. A few students will be brave enough to take on the question with statements such as:

- “Because these characters are nothing like Lenny and George in Of Mice and Men…”

- “I am unable to find one iota of author’s craft, but I did find a metaphor.”

- “I am intelligent enough to know that this is not ‘literature’…”

I generally caution my students not to write against the prompt. All the CAPT released exemplars are ripe with praise for each story offered year after year. But I also recognize that calling the stories offered on the CAPT “literature” promotes intellectual dishonesty.

What does this story say about people in general? In what ways does it remind you of people you have known or experiences you have had? You may also write about stories or books you have read or movies, works of art, or television programs you have seen. Use examples from the story to explain your thinking.

Inevitably, a large percentage of students write about personal experiences when they make a connection to the text. They write about “friends who have had the same problem” or “a relative who is just like” or “neighbors who also had trouble”. When I read these in practice session, I sometimes comment to the student, “I am sorry to hear about____”.

However, the most frequent reply I get is often startling.

“No, that’s okay. I just made that up for the test.”

At least they know that their story, “an account of imaginary or real people and events told for entertainment,” is not literature, either.