Anne Frank: The Diary of Young Girl transcends the labels of genre.

Yes, as the title suggests, it is a diary, but it is also a memoir, a narrative, an argument, an expository journal, an informational text, and much more.

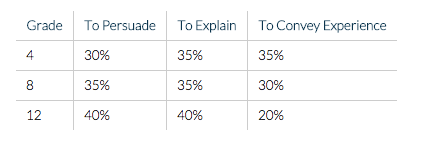

Yet, these genres listed are treated as separate and distinct in the reading and writing standards of the Common Core (CCSS). The standards emphasize the differences between the literary and informational genres. The standards also prescribe what percentages much students should read (by grade 12 30% literary texts/ 70% informational texts), what genres of writing they should practice (narrative, informative/explanatory, argumentative) and the percentages students should expect to communicate in these genres by grade level.

In the real world, however, the differences between genres is not as clear and distinct as neatly outlined in the standards. The real world of Nazi occupied Holland was the setting that produced the defiant Diary of Anne Frank.

On June 12, 1942, Anne Frank received a red and white check autograph book as a birthday gift. This small volume was soon filled by Anne as a diary, the first of three separate volumes, as she her family and friends hid in the secret annex.

A diary is a daily record, usually private, especially of the writer’s own experiences, observations, feelings, attitudes.

Anne’s narrative in these diaries provides a sequence of events and experiences during the two years she spent hiding with others behind the bookcase in the attic where her father had been employed.

A narrative is a story or account of events, experiences, or the like, whether true or fictitious.

In June of 1947 Anne’s father Otto Frank published The Diary of Anne Frank, and it has become one of the world’s best-known memoirs of the Holocaust.

A memoir is a written account in which an individual describes his or her experiences.

In one entry Anne explains she is aware of what was being done with Jews throughout Europe and those who resisted the Nazis. She refers to radio reports from England, official statements, and announcements in the local papers. There are expository style entries throughout the diary that help the reader understand how much she and others knew about the Holocaust:

“Our many Jewish friends and acquaintances are being taken away in droves. The Gestapo is treating them very roughly and transporting them in cattle cars to Westerbork, the big camp in Drenthe to which they’re sending all the Jews….If it’s that bad in Holland, what must it be like in those faraway and uncivilized places where the Germans are sending them? We assume that most of them are being murdered. The English radio says they’re being gassed.” October 9, 1942

“All college students are being asked to sign an official statement to the effect that they ‘sympathize with the Germans and approve of the New Order.” Eighty percent have decided to obey the dictates of their conscience, but the penalty will be severe. Any student refusing to sign will be sent to a German labor camp.”- May 18, 1943

Expository writing’s purpose is to explain, inform, or even describe.

Finally, there are excerpts taken from the diary where Anne makes a persuasive argument for the goodness of people, even in the most awful of circumstances:

“Human greatness does not lie in wealth or power, but in character and goodness. People are just people, and all people have faults and shortcomings, but all of us are born with a basic goodness. If we were to start by adding to that goodness instead of stifling it, by giving poor people the feeling that they too are human beings, we wouldn’t necessarily have to give money or material things, since not everyone has them to give.” March 26, 1944

A persuasive argument is a writer’s attempt to convince readers of the validity of a particular opinion on a controversial issue.

Anne’s opinion about the goodness of people during the horrors of the Holocaust is a remarkable argument.

The Diary of Anne Frank gave rise to other genres. Anne’s diaries served as the source material for a play produced in 1955 and then as a film in 1959.

The genre of The Diary of Anne Frank, however, should not be the focus, or the reason for its selection into a curriculum or unit of study. Instead, it is the quality of the writing from a young girl that makes the diary a significant contribution to the literature of the 20th Century.

Novelist and former president of the PEN American Center, Francine Prose revisited the diary and was “struck by how beautiful and brilliant it is.” Prose’s research on Anne Frank as a writer culminated with her own retelling, Anne Frank: The Book, the Life, the Afterlife, in which she makes a strong case for the literary quality of Anne’s writing:

“And the more I thought about it, the more I realized how rarely people have really recognized what a conscious, incredible work of literature it is.”

In an interview on the PBS website, Prose was asked, “Do you think there is something about Anne Frank’s voice that continues to resonate with young people today?” Her response,

“I do. Because the diary was written by a kid, it is almost uniquely suited to be read by a kid. Salinger and Mark Twain certainly got certain things right about being a kid; but they weren’t kids when they wrote their books. The diary works on so many different levels.”

When selections from The Diary of Anne Frank were first published in the “Het Parool” on April 3, 1946, the historian Jan Romein also recognized how Anne’s young literary voice rose above the inhumanity that caused in her death at 15 years in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. In his review, he writes:

“… this apparently inconsequential diary by a child… stammered out in a child’s voice, embodies all the hideousness of fascism, more so than all the evidence at Nuremberg put together.”

Romein’s review elevates the “apparently inconsequential diary” as testimony in making a legal case against the Nazi regime. It is that power in Anne’s voice that makes her diary a powerful text to offer students, whether it fits the percentages in a CCSS aligned unit of study for an informational text or not.

Her entry on July 15, 1944, written 20 days before she and her family are betrayed to the Nazis reveals yet another genre:

“I see the world being slowly transformed into a wilderness, I hear the approaching thunder that, one day, will destroy us too, I feel the suffering of millions. And yet, when I look up at the sky, I somehow feel that everything will change for the better, that this cruelty too shall end, that peace and tranquility will return once more.”

For there is poetry in that entry as well.