A short-lived category sub-set in a Wikipedia entry set off a feminist firestorm at the end of April. In an editorial for the New York Times titled “Wikipedia’s Sexism“, the writer Amanda Filipacchi noted the removal of women writers from the Wikipedia web page category “American Novelists”; women writers had been regrouped under a new web page, “American Women Novelists”. Filipacchi wrote:

A short-lived category sub-set in a Wikipedia entry set off a feminist firestorm at the end of April. In an editorial for the New York Times titled “Wikipedia’s Sexism“, the writer Amanda Filipacchi noted the removal of women writers from the Wikipedia web page category “American Novelists”; women writers had been regrouped under a new web page, “American Women Novelists”. Filipacchi wrote:

“I looked up a few female novelists. You can see the categories they’re in at the bottom of their pages. It appears that many female novelists, like Harper Lee, Anne Rice, Amy Tan, Donna Tartt and some 300 others, have been relegated to the ranks of ‘American Women Novelists’ only, and no longer appear in the category ‘American Novelists.’ If you look back in the “history” of these women’s pages, you can see that they used to appear in the category ‘American Novelists,’ but that they were recently bumped down. Male novelists on Wikipedia, however — no matter how small or obscure they are — all get to be in the category ‘American Novelists.’ It seems as though no one noticed.”

The category “American Women Novelists” was created by a 32-year-old history student at Wayne State University, John Pack Lambert. His editing was violation of Wikipedia’s rules that categories should not be based on gender.

Yet, this regrouping called attention to other “gender-biased” incidents that have happened at “the free encyclopedia that anyone can edit.” Apparently “anyone” is not editing. In an interview on NPR by Lynn Neary,”What’s In A Category? ‘Women Novelists’ Sparks Wiki-Controversy”, Wikipedia editor Ryan Kaldari admitted:

“Only about 10 percent or less of the editors at Wikipedia are women. And so a lot of times there’s this subconscious, white, male, privileged sexism that exists on Wikipedia that isn’t really acknowledged.”

While that admission is startling in its honesty and frightening implications about editors at Wikipedia, another interesting story seems to have gone unnoticed. At age 12, Wikipedia is “coming of age”. The repercussions from this incident mark another step towards Wikipedia’s gradual movement towards acceptability; Wikipedia is learning how to becoming academically legitimate.

For example, what difference would it have made years or even several months ago if a Wikipedia editor had decided to create gender based subsets within categories if the Wikipedia was used primarily as a source to “settle a bet with a roommate“? In addition, as the web becomes more collaborative in the sharing of information, is the information on Wikipedia less valid because the more than one writer is responsible for the article? Moreover, do the “real time” corrections like those made every day on Wikipedia improve the validity of information available or do these corrections even matter since research from Ohio State University shows that many people cling to misinformation despite corrections? And up until last April, would any scholar or academic have cared how a Wikipedia editor organized one of the 4,325 categories currently available?

In the article “Wikipedia’s Woman Problem”, James Gleick in the New York Review of Books explained that Wikipedia has logged thousands of pages of discussions on categories:

“It’s fair to say that Wikipedia has spent far more time considering the philosophical ramifications of categorization than Aristotle and Kant ever did.”

Aristotle? Kant? Wikipedia is philosophical? That sounds almost scholarly.

Gleich makes the point that categories matter to Wikipedia:

“Categories are a big deal. They are an important way to group articles; some people use them to navigate or browse. Categories provide structure for a web of knowledge—not a tree, because a category can have multiple parents, as well as multiple children.”

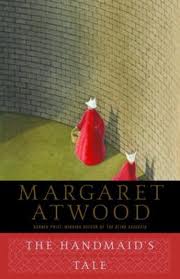

The creation of the “American Women Novelist” category briefly separated Toni Morrison, Anne Rice, Nora Roberts, and Annie Dillard from their category counterparts such as Isaac Asimov, Ernest Hemingway, Hunter S. Thompson, Truman Capote,and Zane Gray. The result was that many scholarly people did care, especially female novelists. Joyce Carol Oates (novelist, short story writer, playwright, poet, literary critic, professor, editor) expressed her views on Twitter:

“Wikipedia bias an accurate reflection of universal bias. All (male) writers are writers; a (woman) writer is a woman writer.”

“New idea for Wikipedia sex-bias: list names alphabetically only of those Americans who ARE NOT writers/ poets.”

Similarly, the novelist Amy Tan, mentioned in the NY TImes editorial by Filipacchi, tweeted her response:

#WikipediaFail I have been reduced to a Lady Novelist. American novelists=only men. 1990s ghettoization returns!

These comments among others are an indication of broader academic conversations generated by Lambert’s changes to the “American Novelists” page and the exponential growth of information available online today. Who is in charge of information, the organization of information, and the accuracy of information? Salon’s Andrew Leonard’s considers an argument that the editing process for Wikipedia entries is public and that the process of continuous editing brings about accuracy. In his commentary “Wikipedia’s Shame” Leonard points out:

“…hardcore Wikipedia advocates argue that no matter how dumb or ugly the original bad edit or mistake might have been, the process, carried out in the open for all to see, generally results, in the long run, in something more closely resembling truth than what we might see in more mainstream approaches to knowledge assembly.”

But this is not the only incident involving authors and their dissatisfaction with decisions by Wikipedia, and gender bias is not the only controversy. There was also a recent incident involving the novelist Philip Roth. In August 2012, Roth contacted Wikipedia about a misstatement on an entry dedicated to his novel The Human Stain. Wikipedia would not authorize the change, and Roth wrote about the editors’ decision in an open letter published in The New Yorker:

SEPTEMBER 7, 2012

Dear Wikipedia,

I am Philip Roth. I had reason recently to read for the first time the Wikipedia entry discussing my novel “The Human Stain.” The entry contains a serious misstatement that I would like to ask to have removed. This item entered Wikipedia not from the world of truthfulness but from the babble of literary gossip—there is no truth in it at all.

Yet when, through an official interlocutor, I recently petitioned Wikipedia to delete this misstatement, along with two others, my interlocutor was told by the ‘English Wikipedia Administrator’—in a letter dated August 25th and addressed to my interlocutor—that I, Roth, was not a credible source: ‘I understand your point that the author is the greatest authority on their own work,’ writes the Wikipedia Administrator—’but we require secondary sources.'”

Really? The primary word of the author requires secondary sources? That definitely sounds like Wikipedia’s step towards the scholarly; the kind of instructions a teacher might given to a student doing a research paper. With Roth’s situation, however, the editor’s decision seems incongruous, and the explanation reads more like text written by George Orwell, author of the prescient novel 1984.

If that Wikipedia’s editor’s response is Orwellian, then consider another comment made by Wikipedia editor Kaladari that the “American Woman Novelist” vs. “American Novelist” controversy has “about 33,000 words of discussion on it which is quite a lot.” Then he added, “It’s actually more than the novel Animal Farm.”

Mr. Kaladari’s comparison may not have been intended to be ironic, but Orwell’s allegorical novel Animal Farm about a brutal regime that tries to rewrite history may be closer to this heart of this incident that readers realize. Think back to high school and remember the revolutionary speech by the pig, Old Major:

“There, comrades, is the answer to all our problems. It is summed up in a single word–Man.”

“Exactly,” respond female writers everywhere.