In the film Looking for Richard, his tribute to Shakespeare’s historical play Richard III, Al Pacino asks a tourist standing on a street in Manhattan, “What do you know about Shakespeare?”

“Shakespeare? He’s our greatest export!” replies the Brit reaching into his wallet for a credit card. On the credit card was the Flower portrait of Shakespeare as a security hologram. Rotating the card allowed the camera to pick up the image of Shakespeare, who appeared to be winking at the viewer.

As an export, Shakespeare sells. His image, in any one of three possible portraits, is plastered on mugs, teapots, coasters, coins, rugs, and notebooks. His verses are truncated to fit the length of garden stones, pens, bracelets, Ipad cases, and T-shirts. I personally own six scarves with images from his plays or verses from his poems.

There are some more unusual, and certainly less dignified, items available as well for those bard-idolators:

Shakespeare Insult Gum-each box contains two gum balls and a wonderful Shakespearean insult;

Shakespeare Insult Gum-each box contains two gum balls and a wonderful Shakespearean insult;

A Shakespeare Celebriduck-Yes, Shakespeare has been turning into a quacking bard;

A Shakespeare Tissue box cover-Tissue fly from his nose as fast as verses from his pen.

As a product, Shakespeare appeals to a niche market, but given the amount of Shakespeare paraphernalia on the web, that niche market must be very profitable.

Today marks Shakespeare’s 448th birthday. This past month, I have been sell-a-brating Shakespeare in each of my English classes.

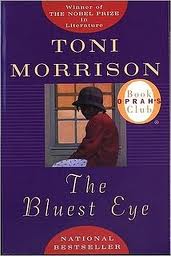

Selling Shakespeare is one of the pleasures of teaching English at the high school level. This year, I have “sold” Othello, King Lear, and Hamlet to the Advanced Placement English Literature class, and I am presently selling Macbeth to sophomores while at the same time selling Romeo and Juliet to freshmen.

Once students get past the Prologue; past witches meeting on a heath; past the Ghost’s appearance on the ramparts; past Act I, scene i; I am on auto-pilot. English teachers accumulate Shakespeare materials in the form of lesson plans, essay prompts, quizzes, audio-tapes, film clips and activities that be pulled out at a moment’s notice. In addition, there are numerous clever resources or plans on the web to access. This past year, I added lesson plans from the websites that featured The Macbeth Tango, Romeo and Juliet on Facebook, and Stick Figure Hamlet.

Of course, the best way to sell Shakespeare to students is to have them attend a well-acted live performance . If there is no performance in the area, a DVD or video streamed production, and they are readily available on Netflix, Amazon, and PBS, of one of the many adaptations of Shakespeare’s plays helps engage students. There are websites that list over 400 feature length films or TV shows that bear his name, so there are many options as to which versions might be used.

However, nothing can replace having students reading and acting out the play in class. Without equivocation, all students are initially terrible at reading Shakespeare cold. Nevertheless, almost every student eventually wants a chance to “strut and fret their hour upon the stage.” Even the brilliant Kenneth Branaugh, now instantly recognizable to my students as “that guy who plays all those characters” in film productions of Hamlet,Othello, and Much Ado About Nothing, recalls in an interview how his first exposure to Shakespeare came in a class where everyone read from The Merchant of Venice. Kenneth remembered being terrified doing it, and that he “didn’t understand the language.” But having survived that experience, he quickly developed the acting bug.

All this exposure to Shakespeare in high school does have an effect on his “brand” or name recognition. Recent reports estimate that Shakespeare’s brand is worth over $600 million, twice the amount of Elvis and Marilyn combined. According to the website Campaign Brief, Shakespeare is the best-selling author of all time, with book sales estimated between two and four billion. In contrast, J.K. Rowling’s unit sales are estimated to be less than 450 million. The company Brand Finance was commissioned to determine the commercial value of Shakespeare’s name. Tim Heberden, managing director of Brand Finance in Australia reported: “Not only do these figures make the Shakespeare brand one of the strongest in the world, but it also shows the potential commercial value the Shakespeare name has garnered.” His firm awarded Shakespeare a triple AAA rating noting that the brand could potentionally rise to 1 billion.

I believe that high school English teachers have had a direct hand in this industry. Shakespeare sells very well, because we have sold him very well. For us, the reward is spreading the poetry and drama of the bard, but for those who are literally selling Shakespeare, we have most certainly “put money in thy purse!”