For teachers who are looking for guidance on how to teach informational texts at the high school level, there is a model lesson on Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address at the EngageNY website. The text of the speech delivered by Lincoln on November 19, 1863, is short enough to fit on two pages or two bronze plaques on a memorial on the battles grounds in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. With 272 artfully crafted words Lincoln reframed the objectives of the Civil War while restating the principles of the equality of man. The opening six words are iconic, the closing asyndeton, “and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth” is inspiring. The choice of the Gettysburg Address is laudable and non-controversial as a selection as an informational text. However, this speech is nearing its 150th birthday, and while an understanding of this speech helps students understand who we were as a nation, there are more contemporary speeches that address who we are as a nation today. What other speeches can we offer our students to review for content and style?

I can think of two speeches that have impressed me this school year. One such speech is a commencement address to college students, the other an address of how the power of rock and roll “commenced” and what that meant to an artist. The first speech is formal, running a little under 15 minutes in length, and delivered by Steve Jobs on June 12, 2005, at Stanford University. The second speech is a full 50 minutes delivered on March 15, 2012, by Bruce Springsteen as the keynote address at the South by Southwest Festival in Austin, Texas.

While Jobs engineered his speech into three separate and distinct parts (“Connecting the dots”, “Love and loss”, “Death”), the “Bruce’s” rollicking retelling of his life as a musician is part-explanatory, part-stream of consciousness, and wholly poetic. While Jobs formally and frankly narrated his stories of failure and ultimate redemption in the computer industry, Springsteen peppered his observations with epithets and musical interludes. Both speeches should get a “look-see” by teachers looking to engage students with meaningful informational texts.

Steve Jobs’s commencement address received a great deal of attention after his passing in October 2011. Stanford University has a page on its website that has both the text of the speech and a video of Jobs reading the speech , standing at the podium with his black graduation robe swirling in the breeze. He opened with the story of his adoption and his bold admission that he had dropped out of college because he “didn’t see the point” –this before a crowd of parents and new graduates who had just completed four or more years at one of the country’s more expensive universities!

Shortly after this startling confession, Jobs deftly described how he followed the “dots”, crediting a calligraphy class at Reed College with being the inspiration in developing his sense of sleek design. These “dots” led him to the computer industry when “Woz and I started Apple in my parents garage when I was 20” and that “in 10 years Apple had grown from just the two of us in a garage into a $2 billion company with over 4000 employees.” He professed his failure, the subsequent firing from the company he had founded, as entirely necessary. “I didn’t see it then, but it turned out that getting fired from Apple was the best thing that could have ever happened to me. The heaviness of being successful was replaced by the lightness of being a beginner again, less sure about everything. It freed me to enter one of the most creative periods of my life.”

In contrast to Jobs’s formal delivery, the video of Springsteen’s speech (video with text link on the NPR website) shows him blinking at the cameras wondering why he is up so early (it was noon) gripping the podium and addressing other musicians saying, “Every decent musician in town is asleep, or they will be before I’m done with this thing, I guarantee you. I’ve got a bit of a mess up here.” Several minutes (and epithets and expletives) later, Springsteen states his thesis:

In contrast to Jobs’s formal delivery, the video of Springsteen’s speech (video with text link on the NPR website) shows him blinking at the cameras wondering why he is up so early (it was noon) gripping the podium and addressing other musicians saying, “Every decent musician in town is asleep, or they will be before I’m done with this thing, I guarantee you. I’ve got a bit of a mess up here.” Several minutes (and epithets and expletives) later, Springsteen states his thesis:

“So I’m gonna talk a little bit today about how I’ve put what I’ve done together, in the hopes that someone slugging away in one of the clubs tonight may find some small piece of it valuable. And this being Woody Guthrie’s 100th birthday, and the centerpiece of this year’s South by Southwest Conference, I’m also gonna talk a little about my musical development, and where it intersected with Woody’s, and why.”

Springsteen’ s “dots” began with Elvis and television:

“Television and Elvis gave us full access to a new language; a new form of communication; a new way of being; a new way of looking; a new way of thinking about sex, about race, about identity, about life; a new way of being an American, a human being and a new way of hearing music. Once Elvis came across the airwaves, once he was heard and seen in action, you could not put the genie back in the bottle. After that moment, there was yesterday, and there was today, and there was a red hot, rockabilly forging of a new tomorrow before your very eyes.”

Inspired by Elvis, the six-year-old Springsteen wrapped his fingers around a guitar neck for the first time, and when they wouldn’t fit, “I just beat on it, and beat on it, and beat on it — in front of the mirror, of course. I still do that. Don’t you? Come on, you gotta check your moves!”

Both of these speeches center on the importance of love and the love of one’s profession. Springsteen’s love of music, and his embrace of all musical genres, is lyrical as evidenced by his professed love for Doo-wop, a passage in the speech which aches for an accompanying melody:

“Doo-wop, the most sensual music ever made, the sound of raw sex, of silk stockings rustling on backseat upholstery, the sound of the snaps of bras popping across the USA, of wonderful lies being whispered into Tabu-perfumed ears, the sound of smeared lipstick, untucked shirts, running mascara, tears on your pillow, secrets whispered in the still of the night, the high school bleachers and the dark at the YMCA canteen. The soundtrack for your incredibly wonderful, limp-your-ass, blue-balled walk back home after the dance. Oh! It hurt so good.”

Jobs’s love of his work at NeXT, at Pixar, at Apple, is less descriptive but equally impassioned, and he challenged the graduates to recognize the importance of loving one’s work:

“Your work is going to fill a large part of your life, and the only way to be truly satisfied is to do what you believe is great work. And the only way to do great work is to love what you do. If you haven’t found it yet, keep looking. Don’t settle. As with all matters of the heart, you’ll know when you find it. And, like any great relationship, it just gets better and better as the years roll on. So keep looking until you find it. Don’t settle.”

Both speeches also focus on change. In the last portion of his speech, Jobs introduced death; in a moment of cheer and celebration, he bluntly talked about death. He was honest with his beliefs, stating how he did not want to die, and he described how the prognosis of pancreatic cancer drove him to seek surgery. His statement, “and I am fine now” is delivered with such confidence, a poignant moment now that he has passed away. However, Jobs was not trying to be maudlin in discussing his, and our own, imminent fate; he deliberately summed up his feelings about death as “the single best invention of Life. It is Life’s change agent. It clears out the old to make way for the new.” Jobs is right about death as a change agent, but as he stood before that crowd gathered for Stanford’s graduation in 2005, he was a live example of a change agent in our lives and the lives of our students.

Springsteen introduced the legacy of Woody Guthrie as his change agent. He explained how in his 20s he read Joe Klein’s Woody Guthrie, A Life, noting that, “Woody’s gaze was set on today’s hard times” and that “Woody’s world was a world where fatalism was tempered by a practical idealism. It was a world where speaking truth to power wasn’t futile, whatever its outcome.” Springsteen explained that although he would cover Woody’s infamous This Land is Your Land, he was never “going to be like Woody” because he was too fond of Elvis and the pop simplicity of his Pink Cadillac, that is until he and Pete Seegar stood up in front of the Lincoln Memorial in 2009 to sing (with the crowd) From California/ To the New York island/ From the Redwood Forest /To the Gulf Stream waters /This land was made for you and me:

“On that day Pete and myself, and generations of young and old Americans — all colors, religious beliefs — I realized that sometimes things that come from the outside, they make their way in, to become a part of the beating heart of the nation. On that day, when we sung that song, Americans — young and old, black and white, of all religious and political beliefs — were united, for a brief moment, by Woody’s poetry.”

Both Jobs and Springsteen ended their speeches with a clarion call. From the industrialist,” Stay Hungry. Stay Foolish. And I have always wished that for myself. And now, as you graduate to begin anew, I wish that for you.” From the musician: “Don’t take yourself too seriously, and take yourself as seriously as death itself. Don’t worry. Worry your ass off. Have ironclad confidence, but doubt — it keeps you awake and alert.”

Could these speeches be “informational texts”-the new CCSS term used to cover all manner of writing other than fiction? While these speeches are most certainly not equal to the eloquence of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, do they have a place in the study of contemporary history? Is the speech that details the development of the Mac with its sleek design and easily used graphic interface, as told by its founder, an informational text? Does the speech that chronicles a musician’s experience with the birth of American rock’n roll and the influence of pop culture qualify as an informational text? Could either speech be a springboard into student research? Could either speech be analyzed for rhetorical structures, word choice, and imagery? Do these speeches inspire the reader?

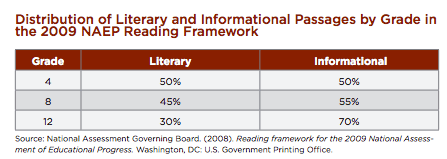

For students in the upper grades of high school, grades 11 and 12, for whom the CCSS suggests 70% of reading should be in the form of informational texts, the answer is a yes, yes, most assuredly yes!

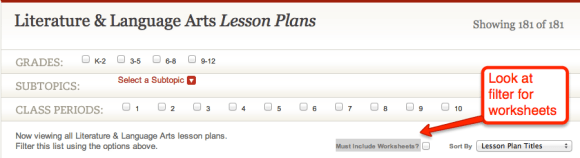

The second problem is a worksheet filter option on the site where lessons can be identified as offering worksheets or not. Worksheets? In the 21st Century, with all the digital possibilities, the National Edmowment for the Humaties is promoting worksheets? Why?

The second problem is a worksheet filter option on the site where lessons can be identified as offering worksheets or not. Worksheets? In the 21st Century, with all the digital possibilities, the National Edmowment for the Humaties is promoting worksheets? Why?

In contrast to Jobs’s formal delivery, the video of Springsteen’s speech (

In contrast to Jobs’s formal delivery, the video of Springsteen’s speech (