Since I write to understand what I think, I have decided to focus this particular post on the different categories of assessments. My thinking has been motivated by helping teachers with ongoing education reforms that have increased demands to measure student performance in the classroom. I recently organized a survey asking teachers about a variety of assessments: formative, interim, and summative. In determining which is which, I have witnessed their assessment separation anxieties.

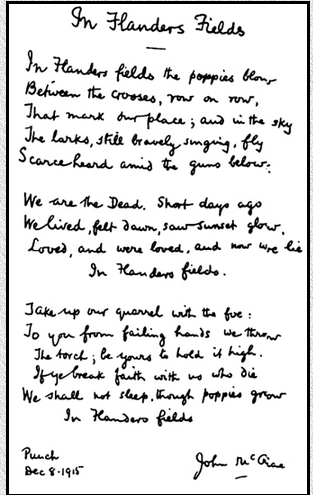

Therefore, I am using this “spectrum of assessment” graphic to help explain:

The “bands” between formative and interim assessments and the “bands” between interim and summative blur in measuring student progress.

At one end of the grading spectrum (right) lie the high stakes summative assessments that given at the conclusion of a unit, quarter or semester. In a survey given to teachers in my school this past spring,100 % of teachers understood these assessments to be the final measure of student progress, and the list of examples was much more uniform:

- a comprehensive test

- a final project

- a paper

- a recital/performance

At the other end, lie the low-stakes formative assessments (left) that provide feedback to the teacher to inform instruction. Formative assessments are timely, allowing teachers to modify lessons as they teach. Formative assessments may not be graded, but if they are, they do not contribute many points towards a student’s GPA.

In our survey, 60 % of teachers generally understood formative assessments to be those small assessments or “checks for understanding” that let them move on through a lesson or unit. In developing a list of examples, teachers suggested a wide range of examples of formative assessments they used in their daily practice in multiple disciplines including:

- draw a concept map

- determining prior knowledge (K-W-L)

- pre-test

- student proposal of project or paper for early feedback

- homework

- entrance/exit slips

- discussion/group work peer ratings

- behavior rating with rubric

- task completion

- notebook checks

- tweet a response

- comment on a blog

But there was anxiety in trying to disaggregate the variety of formative assessments from other assessments in the multiple colored band in the middle of the grading spectrum, the area given to interim assessments. This school year, the term interim assessments is new, and its introduction has caused the most confusion with members of my faculty. In the survey, teachers were first provided a definition:

An interim assessment is a form of assessment that educators use to (1) evaluate where students are in their learning progress and (2) determine whether they are on track to performing well on future assessments, such as standardized tests or end-of-course exams. (Ed Glossary)

Yet, one teacher responding to this definition on the survey noted, “sounds an awful lot like formative.” Others added small comments in response to the question, “Interim assessments do what?”

- Interim assessments occur at key points during the marking period.

- Interim assessment measure when a teacher moves to the next step in the learning sequence

- interim assessments are worth less than a summative assessment.

- Interim assessments are given after a major concept or skill has been taught and practiced.

Many teachers also noted how interim assessments should be used to measure student progress on standards such as those in the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) or standardized tests. Since our State of Connecticut is a member of the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium (SBAC), nearly all teachers placed practice for this assessment clearly in the interim band.

But finding a list of generic or even discipline specific examples of other interim assessments has proved more elusive. Furthermore, many teachers questioned how many interim assessments were necessary to measure student understanding? While there are multiple formative assessments contrasted with a minimal number of summative assessments, there is little guidance on the frequency of interim assessments. So there was no surprise when 25% of our faculty still was confused in developing the following list of examples of interim assessments:

- content or skill based quizzes

- mid-tests or partial tests

- SBAC practice assessments

- Common or benchmark assessments for the CCSS

Most teachers believed that the examples blurred on the spectrum of assessment, from formative to interim and from interim to summative. A summative assessment that went horribly wrong could be repurposed as an interim assessment or a formative assessment that was particularly successful could move up to be an interim assessment. We agreed that the outcome or the results was what determined how the assessment could be used.

Part of teacher consternation was the result of assigning category weights for each assessment so that there would be a common grading procedure using common language for all stakeholders: students, teachers, administrators, and parents. Ultimately the recommendation was to set category weights to 30% summative, 10% formative, and 60% interim in the Powerschool grade book for next year.

In organizing the discussion, and this post, I did come across several explanations on the rational or “why” for separating out interim assessments. Educator Rick DuFour emphasized how the interim assessment responds to the question, “What will we do when some of them [students] don’t learn it [content]?” He argues that the data gained from interim assessments can help a teacher prevent failure in a summative assessment given later.

Another helpful explanation came from a 2007 study titled “The Role of Interim Assessments in a Comprehensive Assessment System,” by the National Center for the Improvement of Educational Assessment and the Aspen Institute. This study suggested that three reasons to use interim assessments were: for instruction, for evaluation, and for prediction. They did not use a color spectrum as a graphic, but chose instead a right triangle to indicate the frequency of the interim assessment for instructing, evaluating and predicting student understanding.

I also predict that our teachers will become more comfortable with separating out the interim assessments as a means to measure student progress once they see them as part of a large continuum that can, on occasion, be a little fuzzy. Like the bands on a color spectrum, the separation of assessments may blur, but they are all necessary to give the complete (and colorful) picture of student progress.

We have well over 100 copies of The Curious Incident of the Dog in the NightTime in our book room. They are a collection of books purchased at book sales ($1-$3 a copy) throughout the state of Connecticut for the past five years. These copies are most likely the discards from book club members who, 10 years after its original publication date (2003), donated their used copies. The only problem in locating copies of the text at a book sale is determining on which genre table the copies will be shelved. The novel is classified as a mystery, but it is also considered a young adult novel or trade fiction, and was

We have well over 100 copies of The Curious Incident of the Dog in the NightTime in our book room. They are a collection of books purchased at book sales ($1-$3 a copy) throughout the state of Connecticut for the past five years. These copies are most likely the discards from book club members who, 10 years after its original publication date (2003), donated their used copies. The only problem in locating copies of the text at a book sale is determining on which genre table the copies will be shelved. The novel is classified as a mystery, but it is also considered a young adult novel or trade fiction, and was