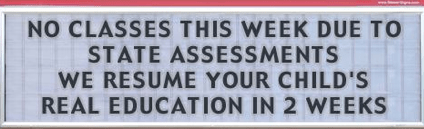

Here is an educational policy riddle: How much background knowledge does a student need to read a historical text?

According to New York Engage website: None.

The Common Core State Standards (CCSS) are being implemented state by state, and there is an emphasis from teaching students background knowledge to teaching students skills, specifically the skill of close reading.

The pedegogy is explained by The Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC):

Close, analytic reading stresses engaging with a text of sufficient complexity directly and examining meaning thoroughly and methodically, encouraging students to read and reread deliberately. Directing student attention on the text itself empowers students to understand the central ideas and key supporting details. It also enables students to reflect on the meanings of individual words and sentences; the order in which sentences unfold; and the development of ideas over the course of the text, which ultimately leads students to arrive at an understanding of the text as a whole. (PARCC, 2011)

There are many lessons that strongly advocate the use of close reading in teaching historical texts on the EngageNY.com website, including a set of exemplar lessons for Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address promoted by CCSS contributor and now College Board President, David Coleman. The lesson’s introduction states:

The idea here is to plunge students into an independent encounter with this short text. Refrain from giving background context or substantial instructional guidance at the outset. It may make sense to notify students that the short text is thought to be difficult and they are not expected to understand it fully on a first reading–that they can expect to struggle. Some students may be frustrated, but all students need practice in doing their best to stay with something they do not initially understand. This close reading approach forces students to rely exclusively on the text instead of privileging background knowledge, and levels the playing field for all students as they seek to comprehend Lincoln’s address.

The lesson plan is organized in three sections. In the first, students are handed a copy of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address and perform several “cold” readings, to themselves and then with the class.

Lesson Plan SECTION 1 What’s at stake: a nation as a place and as an idea

Students silently read, then the teacher reads aloud the text of the Gettysburg Address while students follow along.

- Students translate into their own words the first and second paragraph.

- Students answer guiding questions regarding the first two paragraphs

Please note, there is no mention of any historical context for the speech. Students will come to this 273-word speech without the background knowledge that the Battle of Gettysburg was fought from July 1 to July 3, 1863, and this battle is considered the most important engagement of the American Civil War. They will not know that the battle resulted in “Union casualties of 23,000, while the Confederates had lost some 28,000 men–more than a third of Lee’s army” (History.com). They will not know how the Army of Northern Virginia achieved an apex into Union territory with “Pickett’s Charge,” a failed attempt by General George Pickett to break through the Union line in South Central Pennsylvania, and that the charge resulted in the death of thousands of rebel soldiers. They will not know how the newly appointed Major General George Gordon Meade of the Army of the Potomac met the challenges of General Robert E. Lee by ordering responses to skirmishes on Little Round Top, Culp’s Hill, and in the Devil’s Den. They will not know that Meade would then be replaced by General Ulysses S. Grant in part because Meade did not pursue Lee’s troops in their retreat to Virginia.

Instead of referencing any of this historical background, the guding questions in the lesson’s outline imagine the students as blank slates and mention another historical event:

A. When was “four score and seven years ago”? B. What important thing happened in 1776?

The guiding responses for teachers seem to begrudge an acknowledgement that keeping students bound to the four corners of a text is impossible, and that, yes, a little prior knowledge of history is helpful when reading a historical text:

This question, of course, goes beyond the text to explore students’ prior knowledge and associations. Students may or may not know that the Declaration of Independence was issued in 1776, but they will likely know it is a very important date – one that they themselves have heard before. Something very important happened on that date. It’s OK to mention the Declaration, but the next step is to discover what students can infer about 1776 from Lincoln’s own words now in front of them.

In addition, there are admonishments in Appendix A of the lesson not to ask questions such as, “Why did the North fight the civil war?”

Answering these sorts of questions require students to go outside the text, and indeed in this particular instance asking them these questions actually undermine what Lincoln is trying to say. Lincoln nowhere in the Gettysburg Address distinguishes between the North and South (or northern versus southern soldiers for that matter). Answering such questions take the student away from the actual point Lincoln is making in the text of the speech regarding equality and self-government.

The lesson plan continues:

Lesson Plan SECTION 2 From funeral to new birth

- Students are re-acquainted with the first two paragraphs of the speech.

- Students translate the third and final paragraph into their own words.

- Students answer guiding questions regarding the third paragraph of the Gettysburg Address.

Please note this does not provide the context of the speech that was given that crisp morning of November 19, 1863, at the dedication of the National Cemetery on a damp battlefield that only months before had been dampened red with the blood of tens of thousands of soldiers from either side. The students would be unaware that Lincoln had taken the train from Washington the day before and was feeling slightly feverish on the day of the speech. There is some speculation that he may have been suffering from the early stages of smallpox when he delivered the speech reading from a single piece of paper in a high clear voice. The students would not know that Lincoln’s scheduled time at the podium followed a two hour (memorized) speech by Edward Everett, who later wrote to Lincoln stating, “I should be glad if I could flatter myself that I came as near the central idea of the occasion in two hours as you did in two minutes.” The students would not know that many of the 15,000 crowd members did not hear Lincoln’s two minute speech; the 10 sentences were over before many audience members realized Lincoln had been speaking. The students would not know that this speech marked Lincoln’s first public statement about principles of equality, and they would not know that he considered the speech to be a failure.

Lesson Plan SECTION 3 Dedication as national identity and personal devotion

- Students trace the accumulated meaning of the word “dedicate” through the text

- Students write a brief essay on the structure of Lincoln’s argument

The lesson provides links to the five handwritten copies of the text, in the “Additional ELA Task #1: Comparison of the drafts of the speech” so that students can see drafts of the speech and the inclusion of “under God” in the latter three versions. There is also an additional Social Studies task that incorporates the position of respected historian Gary Wills from his book Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Worlds that Remade America. This activity suggests students use excerpts from Wills’s book and an editorial from the Chicago Times (November 23, 1863) to debate “Lincoln’s reading of the Declaration of Independence into the Constitution”. One excerpt from Wills’s book includes the statement,”The stakes of the three days’ butchery are made intellectual, with abstract truths being vindicated.” Finally, here is information about the battle itself; the battle lasted three days and soldiers died.

The enterprise of reading the Gettysburg Address without context defeats PARRC’s stated objective of having the students “arrive at an understanding of the text as a whole”. The irony is that in forwarding their own interpretation of the speech, David Coleman and the lesson plan developers have missed Lincoln’s purpose entirely; Lincoln directs the audience to forget the words of the speech, but never to forget the sacrifices made by the soldiers during that brutal conflict:

The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here.

Lincoln wrote and delivered the Gettysburg Address to remind his audience “that these dead shall not have died in vain”. Analyzing the language of the address isolated from the Civil War context that created the tone and message is a hollow academic exercise. Instead, students must be taught the historical context so that they fully understand Lincoln’s purpose in praising those who, “gave the last full measure of devotion.”

“It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.”

Educational accreditation is the “quality assurance process during which services and operations of schools are evaluated by an external body to determine if applicable standards are met.”

Educational accreditation is the “quality assurance process during which services and operations of schools are evaluated by an external body to determine if applicable standards are met.”