Yesterday, Scott, the social studies teacher, brought an eighth grader into my office to recite a poem. He had arrived unannounced, and the young girl looked uncomfortable standing in front of teachers and 12th grade students. But, she had Scott by her side, and he encouraged her with small nudge. She took a breath, and holding a copy of the poem before her, she began to recite:

In Flanders Fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

No one said anything after she muffled the last line, and there was an awkward pause. So, I asked her to read the last line again, and Scott pointed to the last sentence in the poem.

“Start here,” he told her, and she reread: If ye break faith with us who die /We shall not sleep, though poppies grow/In Flanders fields.

Only then did we all clap. Her relief was evident, and I noted just as they left, “That last line is the most important in the poem.”

Equally important is what Scott did when he supported this student in having her practice reciting a poem aloud to a group of people. Moreover, this Memorial Day weekend is the appropriate time to hear this particular poem read aloud.

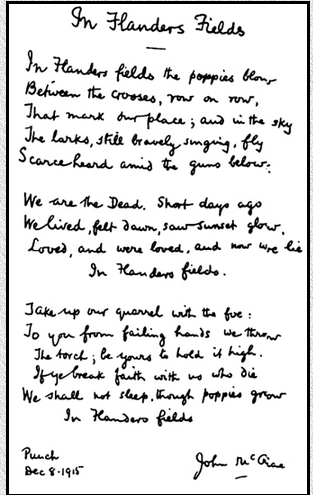

In Flanders Field was composed by John McCrae, a poet and a physician who served in the Canadian army in World War I.

The most common account of the poem’s origin is that McCrae was sitting in the back of an ambulance after the Battle of Ypes in Belgium, when he scripted the poem on May 3, 1915, as a eulogy for his close friend Alexis Helmer, who was killed during the battle the day before.

There are other accounts that McCrae was unhappy with the poem and crumpled the paper before it was retrieved by another soldier who was so impressed that he committed it to memory. Another story is that McCrae had worked on the poem for months after the Battle of Ypes. Most stories about the poem agree, however, that McCrae was struck by how quickly poppies quickly grew around the graves of those who died, and he used this striking image that dominates the poem.

So powerful was this image of a brilliant red poppy that American professor Moina Michael promoted the wearing of red poppies year-round to honor the soldiers who died in the war.

By 1922, the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) adopted the poppy as its official memorial, and when fresh poppies could not be found to sell as tributes, artificial poppies were made by veterans groups. These poppies are called “buddy poppies” and, according to the information on the VFW website, the proceeds from their sale,

“provides compensation to the veterans who assemble the poppies, provides financial assistance in maintaining state and national veterans’ rehabilitation and service programs and partially supports the VFW National Home for orphans and widows of our nation’s veterans.”

I appreciate Scott encouraging his student to share the poem. Hearing her read, “If ye break faith with us who die/We shall not sleep” reminded us listening to remember those who made the ultimate sacrifice for their country. The image of those red poppies, those blooming on Flanders Field or those buddy poppies taken from the hand of a veteran this coming Memorial Day, remind us as well.